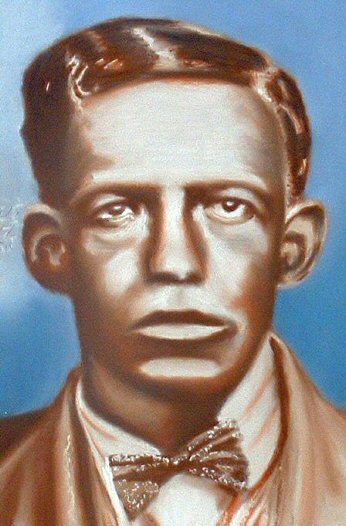

Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Blues At Sea |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Introduction Although the sea-shanty is a form of work-song and the latter is a universal phenomenon in one form or another, the 'shanty is never ascribed any origins from the African continent. For whatever reasons, the various versions of the beginnings of the shanty point to many a geographical birthplace - except Africa. In fact it is not until African slaves were forcibly removed from their homelands that they got involved with work-songs of the sea. Two main areas included the West Indies. On adoption of the English language, that of their 'owners', many West Indian shanties appeared which survived the slaves' emancipation. The other main area was the United States where Africans developed work-songs in their version of English, which were later to form part of the Blues originating in the Deep South. Singing as they work, is a custom that sailors must have practiced since time immemorial. The first reference to a shanty seems to be in the fifteenth century, according to Hugill. But generally speaking, shanties don't seem to have been well-established until the end of the 18th century and became more widespread in the 1830's, when "... reference to shanties and shantying entered literature," (1). The earliest reference in print might well be "On the voyage to Jamaica in the 'Edward Merchantman', in the year 1811," (2) as Hugill supposes; on this occasion. On arrival, the crew vacated and left the unloading to black workers who "... beguiled the time by one of them singing one line of an English song, or a prose sentence at the end of which all the rest join in a short chorus." (3). Although such a description could easily fit black work-songs in the Southern states, generally, the verses quoted are very much in the shanty idiom and not discernibly, in print, black or negroid. Of course as time went by, this situation changed and many shanties, even in print, are obviously sung by blacks, even if the lyrics originated elsewhere. The point being that how they sang shanties might have vestigial African influences but what they sang came from other cultures. How these shanties came into contact with the Blues, I will cover in an exploration of the possible routes of oral transmission and some influences from broadside ballads, music hall, as well as black work songs. Many of the concepts of the latter found their way into the Blues via the sea shanty. Concepts, such as "if the sea/ocean was whisky and I was a duck", and "I got a girl six (up to ten!) feet tall, sleeps in the kitchen with her feet in the hall", were alien to the tribes of West Africa from whence the great majority of U.S. slaves originated. These and other verses will be considered in depth in chapter III while the imagery of an extravagant burial, after a life of poverty and deprivation by digging the grave with a silver spade, seems to have British origins. This image and the idea of lowering the coffin with a golden chain was to appear in many shanties (or different versions of a few) and inspired the Blues singer, especially in Texas. Because of its obvious popularity, this phenomenon warrants a chapter of its own. Other sources for the shanties have been claimed as Latin-American countries, folk songs from Northern Europe and the Mediterranean, amongst others. Under the heading, 'Afro-American origins' Hugill lists "Plantation songs from the Mississippi and Deep South. Negro work-songs in general, from the Gulf Ports. Cotton Hoosiers' chants (Negro and White), Minstrel songs." (4). He also includes work-songs from the American railroads. But while cotton-hoosiers' chants, work-songs from the Gulf ports and elsewhere, etc. could have remnants from Africa in their make-up, via socio-cultural connections and musicological ones, the lyrics emanated from U.S. soil - or they appear to. Certainly, by the time the U.S. blacks' work-song had evolved, along with the 'field hollers' from slavery days, into an idiom recognisable as blues, many of the lyrics were influenced and adapted from British song sources. "Negro sailors were never particular where they get their tunes from. The hymns of evangelists like Sankey and Moody were just as suitable for their purposes as music hall songs" (5). As with tunes, so often it was with lyrics. One of these song sources and the way that verses transmitted cross-culturally, I contend, is the sea shanty. This 'lyric-influence' therefore, via the shanty, becomes another important non-African root of the Blues; as I intend to show. © Copyright 1991 Max Haymes.

All Rights Reserved. Notes:

__________________________________________________________________________

Back

to essay overview

Website © Copyright 2000-2012 Alan White. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||