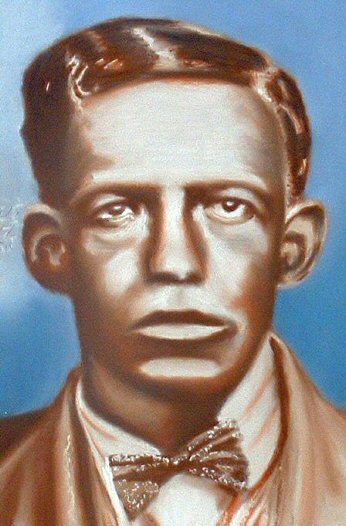

Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

I Need-A Plenty Grease In My Frying Pan |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

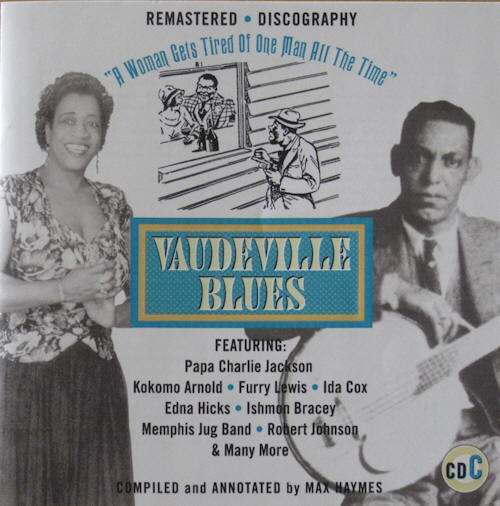

CD C - Eagle Rock Me Mama, Sally Long Me, Too

Although on Salty Dog [Columbia 14143] Clara Smith sang most of Papa Charlie Jackson’s lyrics she gives the song an entirely new setting, a new ‘feel’, with her low-down moaning style backed very ably by Fletcher Henderson on piano. While Kokomo Arnold’s Salty Dog [Decca 7267] features a rural blues atmosphere with his fluid slide guitar at a tempo more akin to that of Jackson. As with Papa Charlie Jackson, Arnold includes a verse about Uncle Bud Russell. (see CD2) But unlike Jackson he includes a second verse, one from Doc. Reese (see CD2) with no attempt at masking the words as Rochelle French had done some two years previously. Indeed, Kokomo Arnold sings the verse with gusto, adding a denigrating epithet:

Papa Charlie Jackson re-appears, this time in a duet with Ida Cox (more from her later). A humorous dialogue which refers to a couple more dances, one of which seems to have ancient links in Native American culture.

The first appearance of Eagle Rock on disc seems to be either Monday Morning Blues [OKeh 4345] by the Norfolk Jazz Quartet in early March, 1921; or Daisy Martin with her Spread Yo’ Stuff [Star Canadian 9115] in early April of the same year. As both dates bear the abbreviated legend ‘c’ for circa, it is quite possible the two records came out at the same time; although composer credit is given to the ‘Norfolk Jazz Quartette’ on the Mary Stafford version (November, 1921) reissued on Archeophone Records. [Footnote 18: See the essential vaudeville-blues reissue on Archeophone 6006. Ain’t Gonna Settle Down(the pioneering blues of Mary Stafford and Edith Wilson) 2 x CD set released in 2008-in amazing sound.] In any event this dance got introduced from minstrelsy and vaudeville sources, in the first instant. While the Norfolk’s song was covered by other singers, Spread Yo’ Stuff makes its lone appearance, via the Daisy Martin opus, in B.&G.R. It is quite likely the very first recording to link the word ‘rock’ to a dance rather than sexual activity! Regaling yet another vamping queen - ‘Susie Brown’ - Ms. Martin sings with piping enthusiasm, an essentially vaudeville performance.

By the mid-1920s, the Eagle Rock was usually joined by another newer dance, as seen with the Ida Cox quote above; the Sally Long and would appear in at least one rural blues, in 1929. This was Black Gypsy Blues [Vocalion 1547] by Furry Lewis (See JSP 7725-A).

Lewis is quite likely to have heard a 1924 recording by Sara Martin called Eagle Rock Me Papa [OKeh 8203].

Both Ms. Martin and Furry Lewis connecting the dance to sexual symbolism. Especially Martin’s phrase ‘Daddy, rock me on your knees’.

While in the earlier 1830s, George Catlin described The Eagle Dance of the Choctaw. “This picturesque dance was given by twelve or sixteen men, whose bodies were chiefly naked and painted white, with white clay, and each one holding in his hand the tail of the eagle, while his head was also decorated with an eagle’s quill. Spears were stuck in the ground, around which the dance was performed by four men at a time, who had simultaneously, at the beat of the drum, jumped up from the ground where they had all sat in rows of four, one row immediately behind the other, and ready to take the place of the first four when they left the ground fatigued, which they did by hopping or jumping around behind the rest, and taking their seats, ready to come up again in their turn, after each of the other sets had been through the same forms”. (93) By the beginnings of the 20th. Century many black citizens could (and sometimes did) claim to have some Native American blood. Most famously, Charley Patton who probably inherited some Choctaw link from his forebears. [Footnote 19: See Red Man And The Blues. Dissertation by Max Haymes. 1991. Lancaster University, reproduced by Alan White on earlyblues.com.] The cultures of the Native American and the African American often became interwoven. In the sources of some of the Brer Rabbit stories, and practices in hoodoo for example. The adopting of the Eagle Rock by blues singers may be added to the list. “Many tribes, among them the Cherokee, and Choctaw, performed Eagle Dances for many different reasons: to create or cement friendships, ensure a successful hunt or battle, cure sickness (particularly ‘eagle sickness’), or make peace between antagonistic tribes. The dances all had in common dancers who moved, and sometimes dressed, like eagles, usually carrying a wand with eagle tail or tailfeathers attached”. (94) The hand and arm movements described by Daisy Martin & Co. are not very different to some of those depicted in the Eagle Dance illustration by Woodrow W. Crumbo - a Potawatomi-Creek - sans the eagle feathers. (see pic. above) The Eagle Rock is alluded to by Bob and Earl in their classic 1960s soul hit Harlem Shuffle where the lady being addressed is encouraged to ‘shake a tailfeather, baby’. Paul Oliver refers to some dances as ‘movements’ which were also incorporated into other dances. “Some dances had a relatively long life, and certain steps and movements were readily transposed to a variety of dance tunes which, in themselves, only enjoyed a brief vogue”. (95) He describes the Eagle Rock movement “with extended arms and bird-like flapping, [which was] … popular for a long time”. (96)

It is quite possible that Ms. Liston is claiming an ancient Native American ancestry for ‘Sally Long’ via the long-standing tradition of the Eagle Dance by way of the Eagle Rock. Floating verses in the Blues are an a essential ‘tool of the trade’ for the early singers. Briefly, if a country blues guitarist is half-way through a song and suddenly his/her inspiration dries up, such a verse which is well-known to the black audience, can be brought into play. One example being:

Another one includes the line ‘If you don’t believe I’m sinking, look what a hole I’m in’. It is quite likely that the majority of these verses emanated from early unrecorded country blues singers. But there is a good chance some first saw the light of day sung by a vaudeville blues performer. In January, 1922, Essie Whitman cut two takes of her If You Don’t Believe I Love You [Black Swan 2036]. She sings floating verses with a novel adaptation of her own.

The omission of the phrase ‘I’ve been’ in the opening line suggest that Ms. Whitman’s audience were already familiar with these lyrics indicating an earlier (than 1922) vintage for this particular floating verse. It could well have been extant at the end of the 19th. Century when Henry Thomas - b.1874 -(see JSP 7730-A) picked it up and reproduced a variant he recorded on Bull-Doze Blues [Vocalion 1230] in 1928. His sound with driving rhythms and stabbing reed pipes/syrinx giving out an archaic atmosphere - in the best sense of the word.

Some 6 weeks later, Mississippi’s Ishmon Bracey (see JSP 7715-E) included similar lines in his awesome Trouble Hearted Blues-Tk.2 [Victor unissued] which sounds equally as archaic.

The verse was also one of only two featured on Stealin’ Stealin’ [Victor V38504] by the Memphis Jug Band recorded just over a fortnight later.

Edna Hicks featured in several musical comedy shows in various theatres in New York, Chicago, and Cincinnati, Ohio. Tragically, she suffered an accident at her home in Chicago, involving gasoline. She was taken to “Provident Hospital where she died of burns; [and was] buried [in the] Holy Sepulchre Cemetery, Worth, IL.”. (105) Like many vaudeville blues singers, Edna Hicks played a piano but only on a demo disc - if at all - at the start of a recording career. She also wrote at least two of her own songs, which she recorded. (106) One of these was Hard Luck Blues [Paramount 12023]. This included a verse which would appear in blues recordings down through the years, with a variation in the second line which seems unique to Ms. Hicks.

Some dozen or so years later, legendary country blues singer Sleepy John Estes (see JSP 7779) cut his Drop Down Mama [Champion 50048] in 1935 which even got issued on a 78 single in the UK!

Estes follows the original phrase which first appeared in Gulf Coast Blues [Paramount 12030] by Texas singer Monette Moore in January, 1923, and just prior to the Bessie Smith version.

In all, there are ten recordings of this song which were all made in the first half of 1923. All were released except the one by Desdemona Jones. (Table 3) Table 3

All of the 9 issued sides, including the one by Edna Hicks, use this phrase and 5 of them followed Esther Bigeou’s slight alteration ‘The men up north sure do make me tired’. Only Bessie adhered to Monette’s original recording. Composer credit is given as ‘Williams’ who is presumably Clarence Williams and who played piano on some of these versions of Gulf Coast Blues. The other self-penned Hicks title is Poor Me Blues [Paramount 12089] also from 1923. This might be distantly related to Poor Me [Vocalion 02651] Charley Patton recorded in 1934, shortly before his death. Actually a different song and apart from the title the Edna Hicks side has only two tenuous links with the Patton recording. To the accompaniment of a fine jazz trio led by Porter Grainger, she introduces her blues.

In 1928, the concluding line in verse 2 was picked up and rearranged as a title by a minstrel/medicine show entertainer known as Hound Head Henry. Now called Cryin’ Blues [Vocalion 1210] he half sings-speaks and ‘cries’ his way through the lyrics including a refrain which Charley Patton incorporated into his own recording 6 years later.

Some 2 months before his death, Charley Patton recorded his version as Poor Me . Whether he was tired at this session on 1st. February, or he was trying to re-capture Hound Head Henry’s ‘crying’ atmosphere is difficult to determine. Certainly his deteriorating heart condition (which killed him in April) was a contributing factor to the atypical ‘lack of fire’ even for 1934. John Fahey said of this song “Neither its structure nor its text is blues … It is probably of Tin Pan Alley origin”. (112) An excellent guitarist himself, Fahey listed the total (then available) recorded output of Charley Patton into six categories. No.5 is titled ‘Miscellaneous’ and the four songs listed-including Poor Me - “do not fit into any of the previous categories and which have been described as problematical”. (113) In any event, Patton added a surreal verse of his own. The implication being that the subject (the singer) has already died and his spirit is looking down through the trees at his last common-law wife, Bertha Lee who survived him by several decades.

Invoking Edna Hicks’ third verse quoted above, from her Poor Me Blues. As the Revenant Records crew point out in the notes to their incredible 7x CD box set of Charley Patton & friends, Walter Davis had sung a variation of this verse in 1932 on his M.&O. Blues No.3 [Victor 213333] (115) with some scintillating piano from Roosevelt Sykes. However, Davis may have heard a live performance by Patton in 1932 prior to recording. In his earlier recording years, he sometimes made the trip from St. Louis (where he had moved to) to his home town of Grenada (pronounced ‘Greneyda’ in the South) in the Mississippi Delta. Patton may have picked up on a floating verse and adapted it to his own personal situation - fear of his imminent demise. Of course there is the possibility that Walter Davis originated this verse himself. Although as one of the Blues’ finest lyricists, this seems to be out of context with his theme on M. & O. Blues No.3. That is, to escape from an ‘unruly’ woman by catching the Mobile and Ohio train to parts unknown. As noted previously on this set, some songs were ‘straight’ covers from vaudeville to country blues. Ma Rainey and Charley Lincoln (CD 2), for example. Others were very similar and can be seen as variations of the same song, as with Ora Alexander and Jed Davenport (CD 1), and the Hound Head Henry/Charley Patton sides (CD 3). Two more are included here. In 1924, Ma Rainey hollered and sang her way through Booze And Blues [Paramount 12242] to the raucous accompaniment of a top rate section of the Fletcher Henderson band, including Charlie Green’s ‘dirty’ trombone. As we have seen, Charley Patton listened to earlier recordings by different blues singers and this Ma Rainey song obviously impressed - and inspired - him enough to do a remake of his 1929 Tom Rushen Blues [Paramount 12877] some five years later as High Sheriff Blues in 1934 for Vocalion. [Footnote 21: “This was noted by Calt & Wardlow in 1988—see King Of The Delta Blues (Rock Chapel Press).” Railroadin’ Some. Ibid. p.282. See bibliography for full details. More details of the other names Patton sings about are in Calt & Wardlow, Ibid.] The earlier piece referred to a local Delta law officer (white) called Tom Rushing to whom Patton gave a copy of the Paramount record. Rushing was proud to relate this to researchers in the 1960s. Rainey’s main biographer, Sandra Lieb, notes that Booze And Blues was “not copyrighted in Ma Rainey’s name, and thus we cannot be sure that she was the original performer,”.(116) While Calt & Wardlow state that Rainey’s song was “credited to T. Guy Saddoth”. (117) I made reference to husband and wife teams as a very popular part of the vaudeville blues in the 1920s (see CD 4). This phenomenon brought to light some more male singers - in addition to Papa Charlie Jackson - in this genre. One of these is the fine example of George Williams who was born in Houston, Texas, “about 1899”. (118) He was usually featured with his wife Bessie Brown (CD 4). As with other of these duos, he gets the odd solo number. On his A Woman Gets Tired Of One Man All The Time [Columbia 14002] he takes a more cynical, but sometimes true, look at married life which seems to be growing stale with the passage of time. Especially when one partner is working at one of the few legitimate jobs open to blacks, to make ends meet.

Although Chris Smith is quite dismissive of the talents of George Williams - and Bessie Brown - I think this is showing some in-built prejudice on his part, which I have to say is not typical of his writings. (120) Comparing this duo unfavourably with the likes of Butterbeans and Susie (CD 4) is being a little disingenuous. Williams and Brown were a long-standing and very popular team in the 1920s, as Chris notes, and I feel sure it was in part to NOT sounding like said Butterbeans and Susie. What these duos included in their dialogue and songs was often of major importance to black listeners - as indeed it is with the blues of the rural singers. Listeners should try and ‘see’ the lyrics through the eyes of an African American, certainly at the time. As Paul Oliver said so many years ago in his groundbreaking book Blues Fell This Morning (121) Chris Smith’s comments on Bessie Brown’s Hoodoo Blues and George Williams’ Chain Gang Blues and their accompaniments are “of more verbal than musical interest” (122) should be seen as a plus rather than a minus aspect. But the listeners can make up their own minds, and I would only add that repeated listenings can be very rewarding. In passing, the famous duo of Leroy Carr and Scrapper Blackwell (see JSP 7710 & JSP 77125) cut an urbanized version in 1929 adapted to their Don’t You Get Tired Of Riding That Same Train All The Time (JSP 7710).

Featuring some excellent cornet by an unidentified player. Twelve years further down the line, the celebrated Robert Johnson used Cox’s definition and added one of his own.

__________________________________________________________________________ Notes:

__________________________________________________________________________ © Copyright 2012 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.

Back

to essay overview

Website © Copyright 2000-2012 Alan White. All Rights Reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1924

marked the debut of the only successful male solo artist in the first

six years of blues recordings (1920-1925): Papa Charlie Jackson - referred

to in my Introduction. Playing a big six-string banjo-guitar he was

very much in the vaudeville blues mould as well as drawing on a

minstrelsy repertoire including a few rural blues sides. One of his

earliest and most popular songs was Salty Dog Blues

[Paramount 12236]. This was covered by a handful of male

artists -including Kokomo Arnold and Leadbelly - and a lone female

version by Clara Smith in 1926. Also in this year, Jackson re-cut his

song with Freddie Keppard’s Jazz Cardinals, laying aside his

instrument.

1924

marked the debut of the only successful male solo artist in the first

six years of blues recordings (1920-1925): Papa Charlie Jackson - referred

to in my Introduction. Playing a big six-string banjo-guitar he was

very much in the vaudeville blues mould as well as drawing on a

minstrelsy repertoire including a few rural blues sides. One of his

earliest and most popular songs was Salty Dog Blues

[Paramount 12236]. This was covered by a handful of male

artists -including Kokomo Arnold and Leadbelly - and a lone female

version by Clara Smith in 1926. Also in this year, Jackson re-cut his

song with Freddie Keppard’s Jazz Cardinals, laying aside his

instrument.