This is the full essay (click

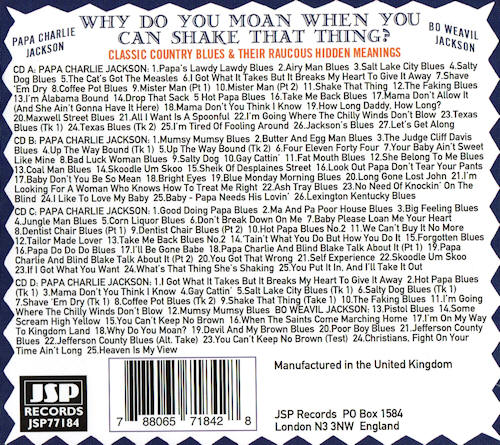

on the links below) published in short form as the liner notes for 'Why Do You Moan, When You Can Shake That Thing?'

the JSP Records 4 CD boxed set. We hope you all

enjoy it.

Essay © Copyright 2014 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.

Website, page design and formatting

© Copyright 2000-2015 Alan White. All Rights Reserved.

www.jsprecords.com

www.redlick.com

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

One of the

interesting facts to emerge from putting Papa Charlie Jackson and Bo

Weavil Jackson together in a CD set, is the obvious different

approaches they applied to the recently-arrived phenomenon - the

country or rural blues. Both artists were growing up in the South

when the Blues were relatively young. Still, there would seem to be

little commonality between William Henry and James Jackson - presumed

to be their respective given names. Apart from sharing a (very

common) surname and both coming from an earlier generation of

singers, of the 19th. Century. A further instance may be

cited insofar they both accompanied themselves on stringed

instruments. Papa Charlie, in the words of Chris Smith

“generally played the banjo-guitar, a hybrid instrument whose six

strings were tuned and fingered like a guitar’s, but whose banjo

body gave it a light, staccato sound.”. (1)

Chris

Smith attributes a birthdate for Papa Charlie Jackson as “c.

1885”. (2) But up to the

present time (26th. January 2014) no one has hazarded

even an approximate year for the initial appearance on the planet of

Bo Weavil Jackson. Judging by some of his recorded repertoire and

along with a solitary ‘head-shot’ picture, he would appear to be

possibly a good ten years older than Charlie. This would make him a

cotemporary of Henry Thomas (b.1874) and a date in the 1870s - maybe

at the beginning of the decade, is my educated guess. Unlike many

early blues singers, Papa Charlie Jackson came from a city - New

Orleans - or an otherwise large urban environment. This is reflected

in his recordings and their musical influences. His affinity with

early vaudeville blues singers

[Footnote

1: See my 4-CD set Vaudeville Blues (Blues Links-Vaudeville &

Rural Blues: 1919-1941) on JSP 77161, issued 2012.]

would seem to

support this. He appeared on 7 sides with Ida Cox, Ma Rainey and

Hattie McDaniel in 1925, 1928 and 1929, respectively. Cutting 74

sides under his own name between 1924 and 1934, only 4 remain

unissued. Together with three with Ida Cox, two with Ma Rainey, and

probably two with Hattie McDaniel, making 81 in total.

Chris

Smith attributes a birthdate for Papa Charlie Jackson as “c.

1885”. (2) But up to the

present time (26th. January 2014) no one has hazarded

even an approximate year for the initial appearance on the planet of

Bo Weavil Jackson. Judging by some of his recorded repertoire and

along with a solitary ‘head-shot’ picture, he would appear to be

possibly a good ten years older than Charlie. This would make him a

cotemporary of Henry Thomas (b.1874) and a date in the 1870s - maybe

at the beginning of the decade, is my educated guess. Unlike many

early blues singers, Papa Charlie Jackson came from a city - New

Orleans - or an otherwise large urban environment. This is reflected

in his recordings and their musical influences. His affinity with

early vaudeville blues singers

[Footnote

1: See my 4-CD set Vaudeville Blues (Blues Links-Vaudeville &

Rural Blues: 1919-1941) on JSP 77161, issued 2012.]

would seem to

support this. He appeared on 7 sides with Ida Cox, Ma Rainey and

Hattie McDaniel in 1925, 1928 and 1929, respectively. Cutting 74

sides under his own name between 1924 and 1934, only 4 remain

unissued. Together with three with Ida Cox, two with Ma Rainey, and

probably two with Hattie McDaniel, making 81 in total.

Two of the most popular

sides Papa Charlie cut were Salty Dog Blues [Paramount 12236]

and Shake That Thing [Paramount 12281] in 1924 and 1925

respectively. He became one of the very few blues artists in the

pre-war era who recorded with jazz players. In 1926 he did a re-make

of Salty Dog Blues [Paramount 12399] accompanied by Freddie

Keppard And His Jazz Cardinals - significantly (?) Jackson did not

play his banjo on this version. Also recorded by several blues

singers including the most memorable by Clara Smith and later Kokomo

Arnold. While Shake That Thing was covered by Ethel Waters

who unsuccessfully tried to claim the song as her own, as well as

versions including Kokomo Arnold, Viola McCoy and Eva Taylor. Papa

Charlie, like several others from an earlier generation of blues

singers like Charlie Patton and Blind Lemon Jefferson, also cut four

excellent gospel sides. Three with some of the finest bottleneck

guitar on record (as on some of his blues) and one played in

‘standard’ or with the ‘naked fingers’ as some pundit once described

it. This latter song I’m On My Way To The Kingdom Land

[Paramount 12390] includes some heavy percussion or ‘stomping his

box’ which may be seen as a precursor of style used by the great

Blind Willie Johnson within a couple of years, on his Let Your

Light Shine On Me in 1929. Or ultimately from master Delta

blues man Charlie Patton himself. Indeed, Don Kent says of his

Devil And My Brown Blues [Vocalion unissued] it is

“imaginative in utilizing different melodies and guitar parts (much

like Charlie Patton), rather than repeating the same riffs

throughout the song with minor or no embellishments.”. (3)

Although

both Jacksons remain shadowy figures, in the case of Papa Charlie

this became slightly less so on the publication of an excellent

article by Paul Swinton in The Frog Blues & Jazz Annual No.2.

It is from this article we learn that Papa Charlie Jackson was “A

neighbour and sometimes playing partner” (4)

of another vaudeville blues singer, Laura Rucker. Although they

never recorded together, as far as we know. But by approaching the

subject with some caution, the odd little biographical snippet may

be gleaned from some of his recordings. For example on Look out

Papa, Don’t Tear Your Pants [Paramount 12553] Jackson reveals he

was the first-born in his family, implying of course the existence

of at least one male sibling. He plays his usual banjo accompaniment

and NOT guitar. B.&G.R. to be adjusted accordingly.

Although

both Jacksons remain shadowy figures, in the case of Papa Charlie

this became slightly less so on the publication of an excellent

article by Paul Swinton in The Frog Blues & Jazz Annual No.2.

It is from this article we learn that Papa Charlie Jackson was “A

neighbour and sometimes playing partner” (4)

of another vaudeville blues singer, Laura Rucker. Although they

never recorded together, as far as we know. But by approaching the

subject with some caution, the odd little biographical snippet may

be gleaned from some of his recordings. For example on Look out

Papa, Don’t Tear Your Pants [Paramount 12553] Jackson reveals he

was the first-born in his family, implying of course the existence

of at least one male sibling. He plays his usual banjo accompaniment

and NOT guitar. B.&G.R. to be adjusted accordingly.

|

scat vocal |

|

|

Spoken: |

Yessir! My pappy’s an old

man. Crazy about young girls. By me bein’ the eldest

son, That made me be crazy [about them] too. Now, I’m gonna tell you all

about my pappy getting’ over that fence. |

|

Vocal: |

Look out, pappy gonna tear your pants; [trousers

in UK]

I wants you to understand.

An old man can’t get over that fence.

Oh! Daddy, don’t tear your pants. |

|

Refrain: |

A-gosh papa, don’t you tear your pants;

I want you to fairly understand.

You know you had a needle an’ you had some thread;

An’ you oughta done sewed them

pants. (5) |

This

is the earliest version on record and in the following decade others

appeared titled Don’t Tear My Clothes. Six to be precise, of

which the Library of Congress side by Willie George Albertine King

(1940) and the Red Nelson Don’t Tear My Clothes No.3 remain

unissued. The version by Billy and Mary Mack is unheard by me.

None of the three recordings I do have include the opening

patter (not surprisingly) of Jackson’s song, or indeed the whole

theme of his song. Basically, an old man visiting a married woman

at her home and being surprised by the return of an angry husband,

makes a break for it across the back yard - tearing his clothes in

his frantic haste. Although Big Bill Broonzy (see JSP 7718, 7750

& 7767) on the State Street Boys 1935 recording - and the first ‘cover’

of the Jackson song - does close with a verse concerning himself and

his ‘buddy’ fighting over another man’s wife which could easily lead

to an incident of fence-leaping to escape! But Bill omitted this

verse some two years later when he re-recorded the song with the

Chicago Black Swans in 1937. This slavishly followed a 1936 disc by

Washboard Sam. So Charlie’s reference to being ‘the eldest son’ is

almost certain to be a fact of his life. From which of course we

can say there was at least another male sibling in his immediate

family.

This

is the earliest version on record and in the following decade others

appeared titled Don’t Tear My Clothes. Six to be precise, of

which the Library of Congress side by Willie George Albertine King

(1940) and the Red Nelson Don’t Tear My Clothes No.3 remain

unissued. The version by Billy and Mary Mack is unheard by me.

None of the three recordings I do have include the opening

patter (not surprisingly) of Jackson’s song, or indeed the whole

theme of his song. Basically, an old man visiting a married woman

at her home and being surprised by the return of an angry husband,

makes a break for it across the back yard - tearing his clothes in

his frantic haste. Although Big Bill Broonzy (see JSP 7718, 7750

& 7767) on the State Street Boys 1935 recording - and the first ‘cover’

of the Jackson song - does close with a verse concerning himself and

his ‘buddy’ fighting over another man’s wife which could easily lead

to an incident of fence-leaping to escape! But Bill omitted this

verse some two years later when he re-recorded the song with the

Chicago Black Swans in 1937. This slavishly followed a 1936 disc by

Washboard Sam. So Charlie’s reference to being ‘the eldest son’ is

almost certain to be a fact of his life. From which of course we

can say there was at least another male sibling in his immediate

family.

Another biographical ‘glimpse’ into the

background of Papa Charlie Jackson can be gleaned from the lyrics of

his Coal Man Blues. [Paramount 12461] Reinforced by a second

banjo player who’s shouted comments add to the authenticity of the

lyrics and the scenario they describe. These comments are listed

below as ‘speech’.

|

1. |

P.C.J. |

I get up early in the mornin’; |

| |

Speech: |

What for, papa? |

| |

P.C.J. |

Sweet mama, then [go] over an’ curry my horse.*

(i.e. groom his horse) |

| |

|

I get up early in the mornin’, sweet mama, then I go an’ curry my horse. |

| |

Speech: |

What [a] job, a dirty job. |

| |

P.C.J. |

‘Cos I don’t want nobody for to be my boss. |

| |

|

|

|

2.

|

P.C.J.

|

Then I pull up to the coal pile; |

| |

Speech: |

What do you do then, papa? |

| |

P.C.J. |

Get me a ton of bituminous coal. |

| |

|

Then I pull up to the coal pile, get me a ton of

bituminous coal. |

| |

Speech: |

You certainly (?) will there, papa. |

| |

P.C.J. |

Then I get on my wagon, then I go peddlin’ coal. |

| |

|

|

|

3.

|

P.C.J.

|

[I] Oughta tell how (?) much [is] this

coal;

|

| |

Speech: |

How much is your coal? |

| |

P.C.J. |

Thirty-five cents a bag. |

| |

|

Oughta tell how

much this coal, thirty-five cents a bag. |

| |

Speech: |

Must be good coal. ?? |

| |

P.C.J. |

Then, if you wanna

know my name, just look round my sack. |

| |

|

|

|

4.

|

P.C.J.

|

I climb on my wagon;

|

| |

Speech: |

What do you do then, papa? |

| |

P.C.J. |

Try my best to sell my coal. |

| |

|

I climb on my wagon, try my best to sell my coal. |

| |

Speech: |

Ah! Sell it, papa. Sell that coal. |

| |

P.C.J. |

My baby’s back home, serving ‘er jelly roll. |

| |

|

|

|

5. |

P.C.J.

|

Now, a lot of you women, some of you-all ought to

be - put in jail;

|

| |

Speech: |

What you want all those women locked up for,

papa? |

| |

P.C.J. |

Now, a lot of you women, some of you-all ought to

be - put in jail. |

| |

Speech: |

What are those women locked up, papa? |

| |

P.C.J. |

From standing on the corner, tryin’ their best to sell keen tales. (?) (6) |

Papa Charlie then goes into a kind of

chant-cum-rap with the unidentified second banjoist interjecting

further comments. Probably invoking a traditional street

cry.

| |

P.C.J. |

I got coal. |

| |

Speech: |

Coal, man! |

| |

P.C.J. |

I’m sellin’ coal. |

| |

Speech: |

Deliverin’ that coal. |

| |

P.C.J. |

I’m sellin’ coal. |

| |

Speech: |

How much is your coal, now? |

| |

P.C.J. |

I’m deliverin’ coal. |

| |

Speech: |

Must be good coal. ?? |

| |

P.C.J. |

Bags are cheap. |

| |

Speech: |

Hot coal. |

| |

P.C.J. |

Bags are cheap. |

| |

Speech: |

????? |

| |

P.C.J. |

I’ve got coal. |

| |

|

I’ve got it sold (?) |

| |

Vocal: |

Baby, baby, baby. Can’t you see your papa’s got

coal? |

| |

|

Doggone your

soul.

(7)

|

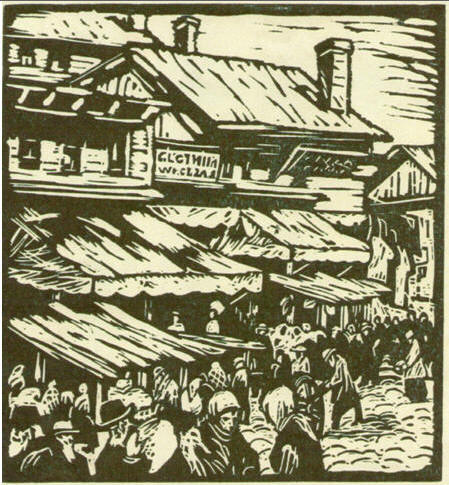

Given

the amount of fine detail that Papa Charlie Jackson offers to the

listener, it would be readily apparent that at some stage he had

indeed been a street vendor of coal; selling it from a horse-drawn

wagon. Also his reference to ‘bituminous coal’ would not be in

generally familiar usage by working class African Americans at the

time and is probably unique in the annals of recorded blues. He

even gives out an address on the Windy City’s famous Maxwell Street

market (alas long demolished) which was a major centre for street

singing blues artists into the early 1970s and ‘80s. Blues was even

heard for the last time (?) on Maxwell at the opening of the 21st.

century according to a report on Wikipedia.

Given

the amount of fine detail that Papa Charlie Jackson offers to the

listener, it would be readily apparent that at some stage he had

indeed been a street vendor of coal; selling it from a horse-drawn

wagon. Also his reference to ‘bituminous coal’ would not be in

generally familiar usage by working class African Americans at the

time and is probably unique in the annals of recorded blues. He

even gives out an address on the Windy City’s famous Maxwell Street

market (alas long demolished) which was a major centre for street

singing blues artists into the early 1970s and ‘80s. Blues was even

heard for the last time (?) on Maxwell at the opening of the 21st.

century according to a report on Wikipedia.

Some

two years previous to his Coal Man Blues, this address

appeared on his Maxwell Street Blues [Paramount 12320] which

might be an actual address or where he intended to make his base for

busking, with his eye on the chance of garnering some more interest

in his playing an singing, and rewarding him accordingly. He was

doing the rounds also on his wagon and ‘pushcart’ at this time

taking in other likely markets as well (selling coal?). But

apparently he’s not just after his daily bread!

| |

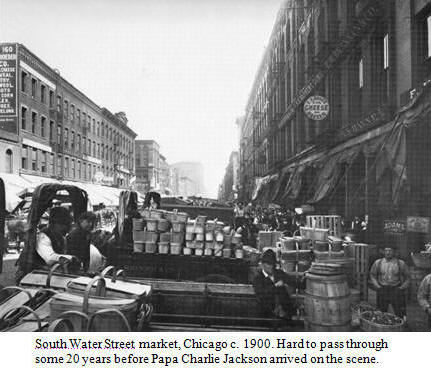

There’s Maxwell Street market, South Water Street market, too. (x 2) |

| |

If you ain’t got no money, the women

got nothin’ for you to do. |

| |

|

| |

Lord, I’m talkin’ about the wagon.

Talkin’ about the push-cart, too. (x 2) |

| |

‘Cos the Maxwell Street [market] so crowded on a

Sunday you can hardly [pass through. |

| |

|

| |

I live 624, mama, an’ I’m talkin’

to you; |

| |

I live 624, Maxwell, mama an’ I’m talkin’ to you. |

| |

‘Cos that’s where I go a-walk, doodly-doodly, how

are you? (8) |

As

already noted Papa Charlie Jackson had recorded with some vaudeville

blue singers including Ma Rainey. There is also a much more

nebulous link between the ‘Mother of the Blues’ (see JSP 7793) and

Bo Weavil Jackson. His very nom-de-plume derives from a 1923

recording she made titled Bo-Weavil

Blues [Paramount 12080] and

was one of her best known songs. As well as including some of the

traditional ‘weevil verses’, Jackson adapts two of Ma Rainey\s own:

Hey, hey bo weevil, don’t sing them

blues no more. (x2)

Bo weevil here, bo weevils

everywhere you go.

I don’t want no man to put no

sugar in my tea. (x 2)

Some of them’s so evil, I’m

afraid they might poison me.(9)

Which Bo Weavil Jackson altered to:

No gypsy woman. No gypsy woman can

fry no meat for me;

Lordy, mama.

No gypsy woman can fry no meat

for me.

I ain’t scared, I’m skittish she

might poison me.

A boll weevil here, a boll weevil

there. Hittin’ farmers everywhere;

The preacher said we got boll

weevils here, boll weevils everywhere.

I get my dream last night it was

all in your flour barrel. (10)

Although the phrase used by Ma Rainey ‘put sugar in my tea’ could be

construed as sexual symbolism on occasion, in this instance it is

far more likely to refer to the all-pervading world of hoodoo. To

‘poison’ somebody in the Deep South during the opening decades of

the 20th. century was to put a spell on them or otherwise

‘fix’ them. Several popular Southern dishes, which included red

beans and rice for example, could include a sample of a woman’s

menstrual blood as part of a mojo hand to ensure her partner does

not stray. Usually by rendering the potentially wayward male as

temporarily impotent, and therefore unable to succumb to the charms

of another woman as his ‘nature was bound to fall’. In Bo Weavil

Jackson’s verse his inclusion of the ‘gypsy woman’ not to fry meat

for him clearly has this danger of being fixed, in mind. Even

though I cannot call to mind the male equivalent in this case!

Although New Orleans and Louisiana generally, are the most

well-known regions in the blues world today; other locations also

had very strong hoodoo reputations. Particularly Beaufort in South

Carolina (home of at least one Dr. Buzzard) and down in Georgia and

Alabama. Tentative stabs at placing Jackson’s home-base have been

stated over the years to be ‘Carolina’ and Mobile or Birmingham in

Alabama. Ma Rainey herself recorded several titles alluding to

superstition and hoodoo from the beginning of her recording career

to the final sessions in 1928. As well as the aforementioned Bo-Weavil

Blues (and its re-make in 1928), these included Lucky Rock

Blues and Toad Frog Blues both from 1924, Louisiana

Hoo-Doo Blues in 1925, plus three from 1928: Black Cat Hoot

Owl Blues , Screech Owl Blues and Black Dust Blues

.

It

was on the streets of Birmingham (‘Magic City’) that Paramount’s

talent scout Harry Charles found Bo Weavil Jackson playing for

nickels and dimes, in the mid-1920s. As indeed, where he found

another rural guitarist Buddy Boy Hawkins who would record in the

following year of 1927. This was during the cross-over from

acoustical to electrical recordings and apparently Charles had

trouble with both these artists in front of the ‘new-fangled’

microphone-both performers “ ‘had difficulty standing still in

front of the microphone ...We had to tie him [Hawkins] up to the

mikes. He walked off. And I put headphones on and it took us all

day to make three or four records’. About Jackson, Charles said,

‘You couldn’t hold him to the mike. He’s be so far from it all the

time’.” (11) The microphone

apparently “ ‘scared a lot of them, even quartets’.” (12)

One of the mainstays of black recordings in Birmingham was the

multitude of excellent a capella quartet groups in the 1920s.

Whichever his place of origin, Bo Weavil Jackson

extended his hoodoo theme on Devil And My Brown Blues [Vocalion

unissued] which was his initial recording for his second and last

session on 30 September, 1926, about a month after his stint for

Paramount; as ‘Sam Butler’. As one of the four major themes in

early blues, hoodoo had evolved from the ancient vodou/voodoo from

West Africa and via Haiti had arrived in the US by 1900. Although

its earlier forms were abundant in the slavery era. One of the main

roles in the African diaspora of gods and spirits was the

trickster. Whilst the crossroads lwa or voodoo spirit Papa Legba

(reappearing as the ‘devil’) and later Brer Rabbit are more familiar

to blues fans, another one who belongs in the same group as Papa

Legba is the spider trickster Ananse/Anansi (both spellings are

used). But although his name is omitted (the Hausa call him Gizo (in this case he survives in the blues more or less as a he was known

to the Ashanti and throughout the Sudanic region in West Africa).

Jackson includes a lyric prevalent in the blues and can be seen as a

floating verse, albeit his answering line (whatever he says at the

beginning of it!) is unique to this singer.

| |

Spider, spider. Spider, spider, crawlin’ on the wall; |

| |

Mm-mmmm. |

| |

Spider, spider. Now, crawlin’ on the wall. |

| |

Cryin’ he’s taxed (?)

but ‘e’s crazy about ‘is alcohol. |

| |

|

| |

I heard a mighty rumblin’ down under the ground; |

| |

Lord, mama. |

| |

Mighty rumblin’ way down

under the ground. |

| |

The boll weevil an’ the devil was stealin’ somebody’s brown. (13) |

Ananse (the Ashanti word) like many gods/demigods

was a shape changer including adopting the form of a bird.

“Ananse is free to modify his own bodily parts and those of others

and to shift them around according to whim and need.”. (14)

So it is an easy interpretation where he transforms into the boll

weevil and meets the Devil down in Hell. Ostensibly to share stolen

sexual pleasures along with the Devil in having their way with a

brownskin woman.

| |

Daddy was low an’ squatty, daddy was [sic] got to

see; |

| |

Lordy, mama. |

| |

Low an’ squatty, daddy was got to see. |

| |

Said he had everythin’

that a poor boll weevil need. (15) |

Ananse “is both fooler and fool, maker and

unmade, wily and stupid, subtle and gross, the High God’s accomplice

and his rival.”. (16)

And “The stories remain bawdy and to everyday sensibilities,

outrageous. Ananse is still a liar and a lecher [while being]

at once creator of order and lawless fool.”. (17)

This High God is Nyame (God of the Sky) and is responsible for

“the creation of human existence [and Ananse] in fact is the agent

of Nyame himself.”. (18)

Yet another blues by Bo Weavil Jackson includes a

reference to a belief in hoodoo which involved the Carolinas. His

first recording of You Can’t Keep No Brown [Paramount 12389]

which is an entirely different song to his Vocalion version, has one

verse running:

| |

I’m gon’ write a letter,

mail it in the air; |

| |

I gon’ write a

letter, gon’ mail it in the air. |

| |

‘Cause [when] the March wind blow, blow news

everywhere. (19) |

Variants of these lines appeared a little later

in blues including those of Garfield Akers and Noah Lewis with

Cannon’s Jug Stompers. Invoking a folk tale from the 1930s, which

described how 2 young black men having no jobs and success at

gambling as a substitute, left their town in North Carolina and

headed south across the State line to the seaport of Beaufort to

visit Dr. Buzzard, an eminent hoodoo doctor. In reply to their

request for a mojo hand to give them a long winning streak at the

gambling tables, Dr. Buzzard said it would cost them $10.00. As the

boys were both broke, he instructed them on how to pay him once they

started accumulating sufficient money. When they could afford the

$10.00 they were to stand and face the rising sun and put the bill

in a sealed envelope. Then they were to throw this up in the air.

After they had done what the hoodoo doctor said, the envelope

immediately disappeared. A few days later the boys heard from Dr.

Buzzard thanking them for the $10.00 payment.

The world of hoodoo crops up in Papa Charlie

Jackson’s very first recording Airy Man Blues [Paramount

12219] in 1924. Part of the refrain runs:

| |

You can get yourself together; |

| |

You can ride with the weather. |

| |

I’m a mean old hairy man. (20) |

This invokes a biblical reference from Genesis,

(xxv.25) where Rebekah (the woman at the well) married Isaac and

gave birth to Esau (the ‘hairy man’) and Jacob. “Rebekah gave

birth to twins. The first born was red and had a hairy body, so

they named him Esau. (The Hebrew word for ‘hairy’ sounds like Seir,

the region of the Edomites, Esau’s descendants.” . (21)

As a young man, and Rebekah’s favourite, “ Jacob said to Rebekah

his mother, Behold, Esau my brother is a hairy man, and I

am a smooth man.”. (xxvii.11)

Esau’s physical appearance may have inspired the

following folk tale collected by the WPA Writers’ Project in 1941.

Coming from the shores of the Tombigbee River in Alabama, this is

titled ‘Wiley and the Hairy Man’. “Wiley’s pappy was a bad man

and no-count. He stole watermelons in the dark of the moon, slept

while the weeds grew higher than the cotton, robbed a corpse laid

out for burying, and worst than that, killed three martins and never

even chunked at a crow [i.e. threw a stone to scare the crow off

the field] So everybody thought that when Wiley’s pappy died he’d

never cross Jordan because the Hairy Man would be there waiting for

him. That must have been the way it happened, because they never

found him after he fell off the ferry boat at Holly’s where the

river is quicker than anywhere else…And they heard a big man

laughing across the river and everybody said, ‘That’s the Hairy

Man’. So they stopped looking.”.

(22)

Wiley was warned by his ‘mammy’ that the Hairy

Man would soon come after him, too. She was “from the swamps by

the Tombigbee and knew conjure.” (23)

This Hairy Man was a shape-changer and he was

“hairy all over. His eyes burned like fire and spit drooled all

over his big teeth.”. (24)

He also had feet like a cow. After Wiley and his mother (with her

conjure powers) were successful in fooling the Hairy Man on two

occasions, they managed to defeat him for good at the third

attempt. Wiley’s mother told him “ ‘That old Hairy Man c’ain’t

ever hurt you again. We done fooled him three times.’ Wiley went

over to the safe and got out his pappy’s jug of shinny

[moonshine] that had been lying there since the old man fell in

the river. ‘Mammy’, he said. ‘I’m goin’ to get hog-drunk and

chicken wild’. ‘You ain’t the only one chile. Ain’t it nice yo’

pappy was so no-count he had to keep shinny in the house?’”

(25)

Another Ma Rainey ‘link’ with Bo Weavil Jackson

occurs in some of the lyrics from her Cell Bound Blues

[Paramount12257] in 1924, and which featured in Jackson’s You

Can’t Keep No Brown [Vocalion unissued] some two years later.

Ma Rainey sang:

| |

I’ve got a mother an’ father lives in a

cottage by the sea; |

| |

Got a mother an’ father livin’ in a cottage by the sea, |

| |

Got a sister an’ brother, wonder do they think of

poor me. (26) |

Sandra Lieb, author of the definitive book on Ma

Rainey, observed that the cottage reference “seems archaic and

outside the blues idiom” .(27)

Yet a dip into Partridge’s dictionary of underworld slang might

suggest otherwise. Although no entry for ‘cottage’, the heading

‘shack’ runs: “ ‘a hut, a very small and humble cottage built of

wood.” (28)

Although probably unique in the Blues via Ma Rainey’s verse, a jazz

standard springs to mind called Cottage For Sale, a Willard

Robison song from 1930 with lyrics by Larry Conley was published.

This had over 100 versions including those by Jack Teagarden, Nat

King Cole, Peggy Lee, Julie London as well as Robison’s original in

1930. Even appearing in the worlds of r ‘n b and rock ‘n roll by

singers such as Charles Brown, Little Willie John, and Chuck

Berry. It is possible Robison was familiar with Rainey’s song.

However widespread in North America, the word ‘cottage’ was replaced

in 1926 by Bo Weavil Jackson. Otherwise his verse runs along

identical lines to Ma Rainey’s:

| |

I got

a mother an’ father, live close to the sea; |

| |

Got a mother an’ father, live close to the sea. |

| |

Got a brother an’ a sister, wonder do they think

of poor me. (29) |

It’s

tantalizing to think he was referring to actual siblings and

possibly younger ones at that. However, this verse (in 2014) is like

a flicker of a dying candle in the dark mystery cloud which

surrounds personal details of James ‘Bo Weavil’ Jackson.

It’s

tantalizing to think he was referring to actual siblings and

possibly younger ones at that. However, this verse (in 2014) is like

a flicker of a dying candle in the dark mystery cloud which

surrounds personal details of James ‘Bo Weavil’ Jackson.

Papa Charlie Jackson had arrived on an I.C. train

from his native New Orleans around the beginning of the 1920s. But

he was not the first in the Windy City. Alberta Hunter (see

Vaudeville Blues. Ibid) was there earlier but by the time

Jackson was getting off his train she had moved east to New York

City where by 1923 some of her most popular contemporaries like

Clara Smith resided.

Like many early rural singers, Bo Weavil Jackson

had a great respect for the vaudeville blues singers who had

preceded him into the recording studios. (Vaudeville Blues.

Ibid.) This would include Papa Charlie who was after all

mainly seen as drawing on the vaudeville and minstrelsy traditions.

Ethel Waters and Clara Smith were just 2 who cut versions of his

repertoire. Another was Sara Martin who had started making records

in 1922. In November 1923, she cut Roamin’ Blues [OKeh 8104]

with just Sylvester Weaver on guitar. One verse ran:

| |

Some would scream ‘high

yellows’, some screamin’ ‘my brown an’ black’; |

| |

Some would’ve scream ‘high yellows’, but give me

my brown an’ black. |

| |

I say, the only colored man that I really like. (30) |

Thus contributing to the socially damaging caste

system so prevalent in the black community which was reflected in

the Blues at the time.

[Footnote 2: See Meaning In The Blues

(p.p.25- 30.Notes. JSP 77141. 4-CDs + 80 page

booklet). On one of the earliest titles, in the spring of 1922, by the

Excelsior Quartette included the line ‘My honey, ain’t you glad

you’re brownskin, chocolate to

the bone’; which 12-string guitarist Barbecue

Bob recorded as Chocolate To The Bone in 1928.]

Some 9 months later in 1924, Papa Charlie Jackson included a rare

ambivalence to this caste system on his first record. As he sang on

Papa\s Lawdy Lawdy Blues [Paramount 12219]:

| |

I ain’t crazy about

no yellers, I ain’t no fool about no brown; |

| |

‘Cos you can’t tell the difference, mama, when

the sun goes down. (31) |

In

1926, Bo Weavil Jackson used Sara Martin’s verse and part of it

became his title-Some Scream High Yellow [Paramount12423].

In April the following year Sara Martin re-made her recording, again

with Sylvester Weaver, as Gonna Ramble Blues. A couple of

months later Clara Smith-Queen of the Moaners-adapted Martin’s lines

for her own individual blues which she introduced with a rare spoken

comment.

In

1926, Bo Weavil Jackson used Sara Martin’s verse and part of it

became his title-Some Scream High Yellow [Paramount12423].

In April the following year Sara Martin re-made her recording, again

with Sylvester Weaver, as Gonna Ramble Blues. A couple of

months later Clara Smith-Queen of the Moaners-adapted Martin’s lines

for her own individual blues which she introduced with a rare spoken

comment.

(Spoken) Some of ya runs around

here. An’ talks about the good-lookin’ high yallers.

An’ some of you raves

about the sealskin browns. Huh! I’m gonna tell you

about these good-lookin’

women, now. (32)

Whereas Clara Smith used part of a jazz outfit

for her musical accompaniment, Sara Martin’s disc was one of the

first vocal and guitar recordings. Although it was Bo Weavil

Jackson’s much harder approach which illustrated the early rural

blues so admirably, featuring something of the Mississippi Delta

sound.

| |

Some screamin’ ‘high yaller’

I screams ‘[I] like a brown’; |

| |

Some scream ‘high yaller’, scream ‘like a brown’. |

| |

A yellow may mistreat you but a black won’t turn

you down. (33) |

Jackson also employed the moan a la Clara Smith

after another verse which was picked up by rock ‘n roll star Chuck Berry some 32 years

later on his Reelin’ And Rockin’.

| |

Sometime I think I will. Then I think that I

won’t. (x2) |

| |

Sometime I think I do so, then I think that I

don’t. |

| |

Mmmmmm-mmmm. Mmmmmmm-mmmm. (x 2) |

| |

Sometime I think I will, an’ then I think that I

won’t. (34) |

The Clara Smith influence is even stronger on

Jackson’s Why Do You Moan? [Paramount 12423], which was his

‘cover’ of Clara’s Awful Moanin’ Blues from 1923.

The main influential two-way stream seems to be

three major vaudeville blues singers-Clara Smith, Ma Rainey and Sara

Martin- and both Jackson’s involvement with hoodoo. Of course these

factors are not peculiar to these singers. Both Charlie Patton and

Charley Lincoln recorded Rainey songs and Bessie Smith along with Ma

Rainey did sides by Papa Charlie Jackson. The latter was originally

from New Orleans and Bo Weavil Jackson has often been cited as from

‘Carolina’. Along with the South Carolina Sea Islands, these

locations were known to feature (and probably still do) some of the

strongest hoodoo traditions in the US. Baby, why do you moan, when

you can shake that thing?

Max Haymes

|

Notes |

|

| |

|

|

1. Smith Chris |

Notes to Papa Charlie

Jackson Vol.1 1924-1926 |

| |

Document CD. [DOCD-5087] 1991. |

|

2. Smith C. |

p.301. |

|

3. Kent Don |

Notes to Times Ain’t

Like They Used To Be- Vol.7. |

| |

[Yazoo CD YA 2067] 2003. |

|

4. Swinton P. |

p.45. |

| |

|

|

5. ‘Look Out Papa Don’t Tear Your Pants’ |

Papa Charlie Jackson vo. bjo., speech.

c. October 1927. Chicago, Illinois. |

|

6. ‘Coal Man Blues’ |

Papa Charlie Jackson vo. bjo.; unk. bjo., speech. |

| |

c. May 1927. Chicago, Illinois. |

|

7. Ibid. |

|

|

8. ‘Maxwell Street Blues’ |

Papa Charlie Jackson vo.bjo.

c. September 1925. Chicago, Illinois |

|

9. ‘Bo-Weavil Blues’ |

Madame ‘Ma’ Rainey acc. by Lovie Austin & Her |

| |

Blues Serenaders: Ma Rainey vo.;

Tommy Ladnier |

| |

cnt.;

Jimmy O’Bryant clt.; Lovie Austin pno. |

| |

December 1923. Chicago, Illinois. |

|

10. ‘Devil And My Brown Blues’ |

Bo Weavil

Jackson vo.gtr.

Thursday, 30th. September 1926. New York City. |

| |

|

|

11. Tuuk van der A. |

p.119. |

|

12. Ibid. |

|

|

13. ‘Devil And My Brown Blues’ |

Ibid. |

|

14. Pelton R.D. |

p. 35. |

|

15. ‘Devil And My Brown Blues’ |

Ibid. |

|

16. Pelton |

Ibid. p.p.27-28. |

|

17. Ibid. |

p.37. |

|

18. Ibid. |

p.47. |

19. ‘You Can’t Keep No Brown

(Paramount) |

Bo Weavil

Jackson vo.gtr.

c. August, 1926. Chicago, Illinois.. |

|

20. ‘Airy Man Blues’ |

Papa Charlie Jackson vo.bjo. |

| |

c. August 1924. Chicago, Illinois. |

|

21. Baldock J.

|

p.34.

|

|

22. Botkin B.A. |

p.682. |

|

23. Ibid. |

|

|

24. Ibid. |

p.683. |

|

25. Ibid. |

p.p.686-687. |

|

26. ‘Cell Bound Blues’ |

Ma Rainey acc. Her Georgia Jazz Band: Tommy Ladnier

cnt.; |

| |

Jimmy O’Bryant clt.; Lovie Austin pno. |

| |

c.

November 1924. Chicago, Illinois. |

|

27. Lieb S. |

p.119. |

|

28. Partridge E. |

p.610. |

|

29. ‘You Can’t keep No Brown’ (Vocalion) |

Bo Weavil

Jackson vo.gtr. (as ‘Sam Butler’)

Thursday, 30th. September 1926. New York City |

|

30. ‘Roamin’ Blues’ |

Sara Martin vo. Sylvester Weaver gtr. |

| |

Friday, 2nd. November 1923. New York City. |

|

31. ‘Papa’s Lawdy Lawdy Blues’ |

Papa Charlie Jackson vo.bjo. |

| |

c. August 1924. Chicago, Illinois. |

|

32. ‘Black Woman’s Blues’ |

Clara Smith vo., speech; Bob Fuller alto.; Porter

Grainger pno. |

| |

Wednesday, 1st. June 1927. New York City. |

|

33. ‘Some Scream High Yellow’ |

Bo Weavil

Jackson vo.gtr. |

| |

c. August 1926. Chicago, Illinois. |

|

34. Ibid. |

|

|

Bibliography |

|

| |

|

|

1. Baldock John

|

Women In The Bible(Miracle Births, Heroic Deeds,

Bloodlust And Jealousy)

|

| |

[Capella. London] 2006. |

|

2. Botkin B.A. (Ed.) |

A Treasury Of American Folklore |

| |

[Crown Publishers. New York] 1944. |

|

3. Lieb Sandra |

Mother Of The Blues (A Study Of Ma Rainey) |

| |

[The University Of Massachusetts Press.

Amherst] 1981 |

|

4. Partridge Eric |

A Dictionary Of The

Underworld |

| |

[Wordsworth Editions. Ware, Hertfordshire] 1989

Rep. 1st.

pub. 1950. |

|

5. Pelton Robert D.

|

The Trickster In West Africa (A Study of Mythic

|

| |

Irony And Sacred Delight) |

| |

[University of California Press. Berkeley.

Los

Angeles. London] 1980. |

|

6. Smith Chris. Tony Russell. |

The

Penguin Guide To Blues Recordings. |

| |

[Penguin Books. London] 2006. |

|

7. Swinton Paul |

The Frog Blues & Jazz Annual No.2. |

| |

[Frog Records Limited. Fleet, Hampshire] 2011. |

|

8. Tuuk van der Alex |

Paramount’s Rise And Fall( A History 0f The |

| |

Wisconsin Chair Company And Its Recording Activities) |

| |

[

Mainspring Press. Denver, Colorado] 2003. |

Discographical details from Blues & Gospel

Records 1890-1943. Robert M.W.Dixon. John Godrich. Howard Rye.

[Clarendon Press. Oxford] 1997.

All corrections/additions by Max Haymes.

Transcriptions by Max Haymes.

20th. March 2014.