Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Pre-war Blues, Dylan's use of, an Introduction

|

|

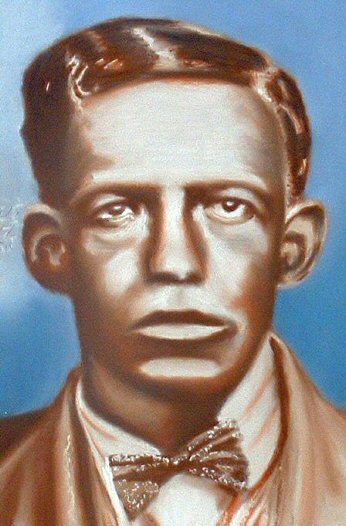

This article is taken from Michael Gray's book "The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia", 2006; updated paperback 2008 © Michael Gray. Michael has kindly agreed for me to publish it on the website. Thanks Michael. Because it’s so crackly on record, so lo-fi, so immured behind a white-noise wall, the black noise that is the pre-war blues can seem inaccessible, unreachable. To be put off by this would be to lose great riches. Sometimes it’s best to play it really loud (and maybe go into the next room): then you’ll hear all the joys and mysteries of esoteric vocals, guitar magic, sheer moody weirdnesses: all the synapse-crinkling giddy-hop that rock’n’roll gave you when you were thirteen. Garfield Akers’ ‘Cottonfield Blues’, especially the transcendent ‘Part 2’, comes across as the birth of rock’n’roll... from 1929! It’s also as incantatory as buddhist chanting or as VAN MORRISON’s ‘Madame George’. (Yet Garfield Akers recorded only four tracks.) Or there’s BLIND WILLIE JOHNSON’s ‘Motherless Children Have A Hard Time’: a record from 1927 that you hear and say of the guitar - if this was achieved then, how come it took thirty years to get to rock’n’roll (or forty years to get to Eric Clapton)? Yet it isn’t that the pre-war blues is proto-rock’n’roll that makes it so uplifting, exciting and vivid. The experience of the encounter is comparable; and the music may hold some of the main ingredients that rock’n’roll returned us to using - but the pre-war blues is a liberation and an enrichment because it’s different, not merely more of the same. These old blues are at once thrillingly exotic and our common heritage. Garfield Akers - a deeply obscure but compelling, intense and distinctive artist who reputedly played around Memphis in the 1920s-30s and again in the 1950s - should have been a tremendous star. His shockingly small number of recordings, or, say, Furry Lewis’ ‘I Will Turn Your Money Green’, are whole new rich seams of their own, a fresh and revelatory 3D world, as glorious as ever Little Richard and Buddy Holly were. This blues world burns with its own heroic energy and vision, and across a musical spectrum of concentrated emotional expression from the utmost in delicacy and finesse to the most searing invocations of cacophonous rapture and pain, while the language of the blues - blues lyric poetry - is one of the great streams of consciousness of 20th Century America: a rich and alertly resourceful African-American fusion and reinvention of the language of the Bible and the dirt road, plantation and medicine show, of the Deep South countryside and the city streets, of 19th Century children’s games, folktales and family lore and African folk-memory: above all the language of the oppressed community and the individual human heart. For Bob Dylan then, as listener and as writer-composer, the specifics of an old record by JIM JACKSON, BLIND BLAKE or MEMPHIS MINNIE yield far richer pleasures than a Johnny Winters or an ERIC CLAPTON performance. This is not a matter of being Politically Correct about authenticity. The whole question of ‘authenticity’ in black music is highly complex and contentious, and involves matters far more consequential than whether Eric Clapton plays the blues. Paul Gilroy’s riveting, if sometimes barely penetrable, essay ‘Sounds Authentic’ cites a number of these issues, across which white-boy debates about authenticity in the blues are bound to stumble rather clumsily, and from which, as Gilroy writes, authenticity ‘emerges as a highly charged and bitterly contested issue.’ It’s an issue too large to detail here. Rather than argue, therefore, as to whether the blues can really be called the blues when purveyed by the Claptons who speed ‘black cultural creation on its passage into international pop commodification’, it seems more useful to suggest, as Bob Dylan probably would, that that sort of blues is simply no longer interesting. It can’t be: such is its shopping-mall forgetfulness that it’s no longer interested - in either the specifics of where it’s come from or of what it’s thrown away. Dylan stands in a very different relation to the blues from that of the white frontmen of the transglobal blues industry. He occupies a position as near to that of the poet or composer (even to the critic) as to the rock’n’roll performer. This difference arises from how he feels about the potency and the eloquence of the old blues records and the expressive vernacular of the world they inhabit. This is why what Dylan wants to do with this immense, rich body of work is experiment in how he might utilise its poetry, its codes and its integrity - to see how these may stand up as building blocks for new creative work - just as he (and just as the blues) uses the language and lore of the King James Bible. He is not concerned with translating a few lowest-common-denominator dynamics of the blues into some MTVable product. First, he claims no blues-singer specialism like a JOHN HAMMOND Jr.: it isn’t, for him, his trademark. His stance does not downgrade blackness per se, therefore: does not carry the inherent sub-text that blues is essentially a matter of ‘style’. It’s telling that on those rare occasions when Dylan performed to specifically black audiences, as in Greenwood Mississippi in 1963 and at the women’s penitentiary in New Jersey during the Rolling Thunder Revue of 1975, he didn’t hesitate to sing about racial politics but chose to do so via his white ‘protest’ songs - ‘Only A Pawn In Their Game’ and ‘Hurricane’ respectively - rather than via blues songs. In contrast, witness the spectacle of John Hammond Jr. imposing his fussy impersonation of an old blues-singer upon the embarrassed black occupants of a Mississippi bar-room for his TV documentary ‘In Search Of Robert Johnson’. Second, Bob Dylan’s interest and special dexterity is in exploring the innards of the blues, taking from the blues the strengths of its vernacular language (to some extent musically as well as lyrically) and building them into the core of his own work - into the machinery of his own creative intelligence. As, in this spirit, he raids the Bible, traditional white folksong and nursery rhyme, so he raids the poetry of the pre-war blues. To do this to such creative profit would be impossible without a mix of curiosity towards and respect for the original contexts from which these things are seized and reworked. This guarantees that, unlike many of those in the global blues industry, Dylan has no interest in seeing the blues ‘deprived of its historical base’ (to quote a Living Blues magazine editorial condemning ‘white blues’ as ‘not blues’). Then there’s a question folklorist Peter Narváez raises when he contends that ‘While historically many forms of downhome blues were played by soloists, and urban blues have always featured individual entertainers… blues fans today recognise blues as a collective activity, that is, a music played by groups who interact among themselves and with audiences.’ We can at once picture Bob Dylan’s response. On the one hand, he too interacts with groups and with audiences. More than ever before, in fact, live audiences seem indispensable to him. Yet he has always believed in the power of the artist with the lone guitar and a point of view. As he said in 1985: ‘I always like to think that there’s a real person talking to me, just one voice you know, that’s all I can handle - Cliff Carlisle... Robert Johnson. For me this is a deep reality: someone who’s telling me where he’s been that I haven’t, and what it’s like there - somebody whose life I can feel.’ At the same time, he knows that the music and the poetry of the blues, its fundamental assumptions, are founded in an Africanness that is itself characterised by ‘groups who interact among themselves and with audiences’ - a theme that the great blues field-recordist and collector ALAN LOMAX, for instance, repeatedly stresses in his 1993 book The Land Where The Blues Began. In other words, the lone blues guitarist would have a different point of view, a different way of expressing him or herself, if the culture from which the blues arose had not been a communal, democratically interactive one - one in which there is almost no hierarchical Artist Up Here and Audience Down There, but, rather, a collaborative performance in which the singer/musician takes cues moment by moment from the dancers/spectators and mingles physically among them, his or her repertoire as much a reaction as an imposition. This is a very different kind of participation from mass-marketed blues performances in which big-name entertainers and high-energy tyro groups please hyper crowds with the most easily magnified clichés of the genre transmitted through flashy guitar-solos and greatest-hits repertoire. Dylan himself talks about the crucialness of old blues couplets (though if he hadn’t, we would know their importance to him from the vast extent to which he has drawn from their wells of material and added to them) in 1985: ‘You can’t say things any better than that, really. You can say it in a different way, you can say it with more words, but you can’t say anything better than what they said. And they covered everything.’ That the young Bob Dylan could insinuate his creative imagination into the world of the older white and black folk artists to enrich even very early songs of his own is not in doubt. What is still more interesting is to look far beyond his very early work to the period from 1964 onwards, when increasingly he freed himself from writing within borrowed folk formats: and to see the huge extent to which, having found the blues powerful and real, and having come to know it so intimately and inwardly, Dylan has drawn deeply from its poetry in creating his own. In the end, it isn’t the main point whether Bob Dylan discovered these people in or around Dinkytown or Greenwich Village, on the radio or via the incredible diverse riches of the blues records avalanching onto vinyl in the 1950s and 60s. Engaging though it is to retrace his routes to these discoveries (see pre-war blues, Dylan’s ways of accessing, also in The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia), in the end, the point is that he made them. And he uses, so singularly, the huge amount he learnt, in the construction of his own extraordinary work. No-one else has used the blues in anything like the way Bob Dylan has. Most people who are ‘into’ the blues take a few standard numbers and riffs from it, and run with them in ever more amplified, clichéd, unrooted ways, or else, at the other extreme, bore us to death with their pedantic archival reproductions of obscurer-than-thou acoustic repertoire. The far smaller number of people whose work is genuinely enriched by the blues are usually musicians, rather than singer-songwriter musicians. But Dylan takes myriad complex treasures from the pre-war country blues, both passionately and quietly, paying them at least as much loving attention as he pays to the vibrant strengths of those 1940s-to-50s electric blues that made possible, more than we knew at the time, all the taken-as-givens of rock’n’roll. And he draws all this cultural richness, the music and the lyric poetry of it, into the very core of his own work. Dylan has worked the blues so strongly and resourcefully that he has given it something back. He inhabits the blues as the best of the old bluesmen themselves did, fusing traditional and personal material into fresh, expressive work of their own, layered with the resonance of familiarity, the subconscious edits of memory and the pleasures of unexpected recognition, sharing the energy that flows between the old and the new, and between the individual and the common culture. He has used the blues with such insistent individuality, yet never in bad faith to the gravitas he found within it, or to the world in which its people had moved. Interviewed in San Diego in autumn 1993, Dylan said: ‘The people who played that music were still around… [in the early 1960s], and so there was a bunch of us, me included, who got to see all these people close up - people like SON HOUSE, REVEREND GARY DAVIS or SLEEPY JOHN ESTES. Just to sit there and be up close and watch them play, you could study what they were doing, plus a bit of their lives rubbed off on you. Those vibes will carry into you forever, really, so it’s like those people, they’re still here to me. They’re not ghosts of the past or anything, they’re continually here.’ It should be no surprise, therefore, to find that blues lyric poetry is everywhere in Dylan’s work: in amongst the New York City hip culture of Dylan 1965 and the radical acid-rock of Blonde On Blonde, in the evangelism at the start of the 1980s and work of more modest, mellowed knowingness right on through to the darkness of Time Out Of Mind and the teeming good cheer of ‘Love and Theft’. Blues lyric poetry runs into the mainstream of Dylan’s work, while he in turn makes a clear creative contribution to this major form of American music. It follows, then, that the more you know of the blues corpus, the more you’ll appreciate Bob Dylan’s extraordinary regenerative use of it; and the better you know Dylan’s output, the better placed you’ll be to hear the blues coursing through it. (See also ‘Call Letter Blues’ & ‘the shock of recognition’. _________________________________________________________________________ [Garfield Akers (c.1900-c.1960): ‘Cottonfield Blues - Part 1’ & ‘Cottonfield Blues - Part 2’, Memphis, c.23 Sep 1929, ‘Dough Roller Blues’ & ‘Jumpin’ And Shoutin’ Blues’, Memphis, c.21 Feb 1930, all CD-reissued on Son House and the Great Delta Blues Singers (1928-1930), Document DOCD-5002, Vienna, 1990. Van Morrison: ‘Madame George’, NYC, 1968, Astral Weeks, Warner Bros WS1768, US (K46024, UK), 1968. Blind Willie Johnson: ‘Mother’s Children Have A Hard Time’ (sic: a mistranscription), Dallas, 3 Dec 1927, Blind Willie Johnson, RBF Records RF-10, NY, 1965. Furry Lewis: ‘I Will Turn Your Money Green’ (2 takes), Memphis, 28 Aug 1928; take 1 issued In His Prime 1927-1928, Yazoo L1050, NY, c.1973; take 2 (the version originally issued on 78) issued Frank Stokes’ Dream...1927-1931, Yazoo L1008, NY, 1968. Paul Gilroy: ‘Sounds Authentic: Black Music, Ethnicity And The Challenge Of A Changing Same’; London: unpublished, 1991, later incorporated into Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, London: Verso, 1993. Bob Dylan: ‘Only A Pawn In Their Game’, Greenwood MS (civil rights rally), 6 Jul 1963 & ‘Hurricane’, Clinton NJ, 7 Dec 1975. John Hammond Jnr.: ‘In Search Of Robert Johnson’; Iambic Production for Channel Four TV, London, 1991. (Greenwood is where Robert Johnson played his last gig, and died.) Paul Garon, ‘Editorial’, Living Blues, nia, & Peter Narváez: both quoted from Narváez’s essay ‘Living Blues Journal: The Paradoxical Aesthetics of the Blues Revival’, collected in Transforming Tradition: Folk Music Revivals Examined, ed. Neil V. Rosenberg, Urbana: University of Illinois Press 1993. Dylan 1st quote, Biograph notes, 1985; 2nd quote in BILL FLANAGAN: Written In My Soul: Rock’s Great Songwriters Talk About Creating Their Music, Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1986; 3rd quote, interview by Gary Hill, San Diego, c.3 Oct 1993 for Reuters, wired to US newspapers 13 Oct 1993.] _________________________________________________________________________ Check out another of Michael's essays: Ghost Trains of the Mississippi Check out Michael's book: 'Hand Me My Travelin' Shoes: In Search of Blind Willie McTell' _________________________________________________________________________

Website © Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White. All Rights Reserved. |