Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

"I Heard The Voice of a Pork Chop" |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

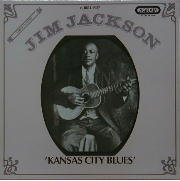

One of the earliest, if not the earliest, recordings of this religious song was made “at or around Chapel Hill and Durham, N.C. and Hampton, Va., in the spring or summer of 1925”. (1) Listed under the heading “Male Negro, v.” (2) the full title is given in the first line: I Heard The Voice Of Jesus Say, Come Unto Me And Rest. This is one of some two dozen other titles recorded at Iowa State University the same time, which “are the earliest non-commercial field recordings of which we have any knowledge.” (3) [Footnote 1] Often used in long-metre or ‘lining out song’ form by black preachers, in 1929 the famous Norfolk Jubilee quartet chose to feature a jaunty piano accompaniment (atypically) and sang their version [Footnote 2] at a much quicker tempo. Possibly, the 'jolly' atmosphere generated (despite adhering to the religious lyric) together with the bass singer/manager Len Williams’ brief scat vocal, could have been inspired by Jim Jackson who cut I Heard The Voice of A Pork Chop [Victor unissued] some 12 months earlier, in January, 1928. [Footnote 3]

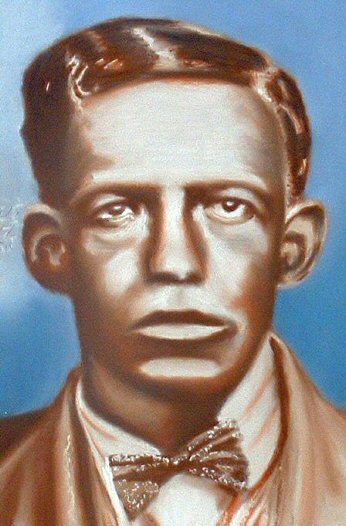

Jim Jackson may have got the idea for this song from a contemporary, songster and bluesman Sam Collins. Born in Louisiana in 1887 (some 3 years younger than Jackson) Collins recorded quite extensively in 1927 and 1931. At one of his earlier sessions he cut Pork Chop Blues [Gennett 6260] which had a definite medicine show-cum minstrelsy feel to it.

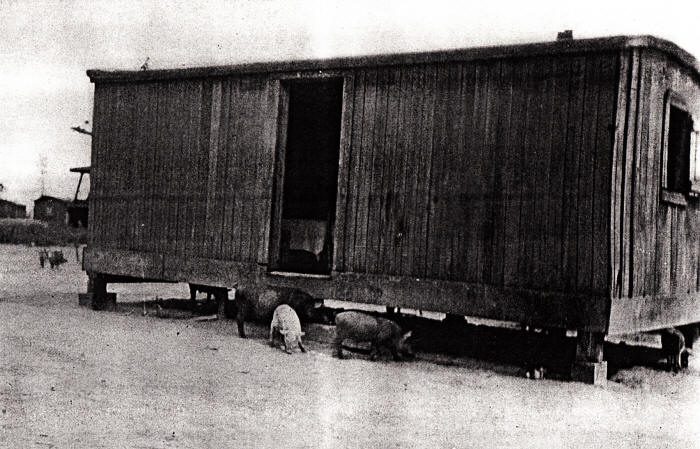

The only other version of Pork Chop Blues I have come across was recorded some nine years later, in 1936. Listed as by "The Two Charlies" it was reissued on a Charlie Jordan CD. Yet THE Charlie Jordan is not present! To the accompaniment of finely-meshed twin guitars they use most of Sam Collins’ lyric but omit the 6th. and 7th. verses. They also introduce ‘Doctor Haigh’ and reveal the singer appearing to be living in an old school bus!

There are in fact another three songs entitled Pork Chop Blues

The earliest, by Bessie Brown, is a different song and a slow blues with fine tenor sax playing by a young Coleman Hawkins, ably backed up by Fletcher Henderson on lively piano.

This 1924 recording may well have sparked the imagination of Sam Collins or Jim Jackson some 4 years down the line. The same comment applies to the Virginia Liston title You Can Dip Your Bread In My Gravy, But You Can’t Have None Of My Chops [OKeh 8218] made in the following year 1925. The next Pork Chop Blues, by Lee Green, is yet a third different song. Green went by the pseudonym ‘Pork Chops’, ‘Pork Chop Jackson’/ ‘Johnson’, and ‘Pork Chop Green(e)’ [sic] (8) and is therefore his own blues. It’s quite likely Green took his name from a railroad freight as “ Pork Chops was an Illinois Central meat train out of Council Bluffs,” (9). This was in Iowa and the Pork Chops ran eastward to Chicago. Pianist Lee Green recorded many sessions from 1929 to 1937 in the Windy City. The song by ‘Funny Paper’ Smith might well be another version of the Collins saga. Sadly, this must remain conjectural as this unissued Vocalion master (along with the remainder of this long session) was destroyed by the company as “the 1935 sessions were found to be faulty.” (10) This affected a total of 18 sides. Hogs were often ‘running in the streets’ according to observations that have been handed down to us from the earlier part of the 19th. Century. This was true of cities like New York as well as those much further south. So it is not surprising that some of this livestock found its way into the woods and forests where they soon became feral. Thus giving access to the poorest section of the southern population as a basic source of their diet. Indeed, hogs still roamed the streets of many a small rural town into the 1920s.

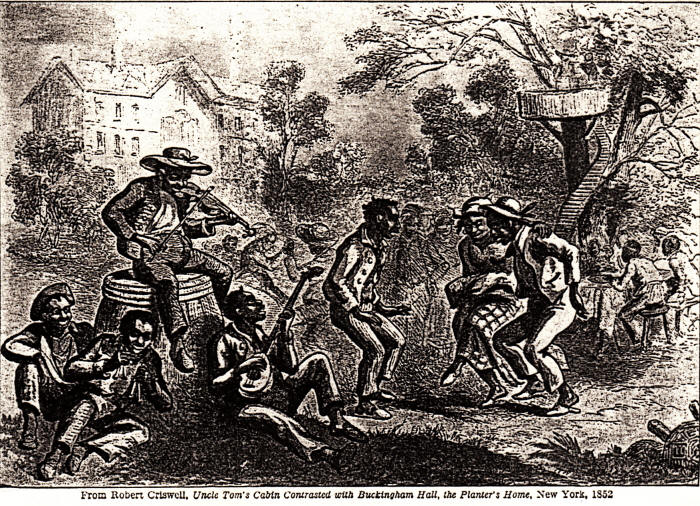

These animals were cheap enough to maintain and many a poor black family would have a hog or a shoat – a recently weaned young pig – rooting around in their back yard. Many of the (usually) white-owned plantations would keep any amount of hogs and 'hog-killing' time meant a big social gathering with music, food and drink as well as some work for blacks. The animal was hung from a tree by its feet and then had its throat slit and left until all the blood had drained away. As an unidentified ex-slave wrote “Hog-killing time was an annual festival.” (11) The author noted: “ When the work was over, the fiddle and banjo inspired the inevitable dance and the songs of slavery were sung again.” (12) The illustration below (from 1852) also depicts a percussionist playing a set of bones in each hand!

Pork chops and pig meat generally became a staple in the diet of blacks in the South, after the Civil War in 1865. [Footnote 4] These cuts of meat quite naturally entered into black song. Thomas A. Dorsey (aka Georgia Tom) once described the term ‘pig meat’ as a reference to a young attractive woman - at least under 40 years old! Female singers also used it in connection with good-looking young men. Older people (both men and women) tried to keep up with “the young folks ways” - not always very successfully.

Nor was it just blues singers who appropriated farmyard symbolism in the 1920s. On the gospel side of the ‘blues coin’ Rev. Emmett Dickinson preached a mini-sermon on the hypocrisy of so-called Christians on Pig Or Pup (or, The Two-Faced Man) in 1930 [Gennett Ge 7145]. Taking his text from the First Book of Kings (18:21) Dickinson finishes his introduction:

Dickinson then goes into his unusual half-chanted, half-spoken subject. After moralizing against wandering married men and women, he really gets in to his stride:

In my own summary, it is tempting to think that with the inclusion of the ‘I heard the voice of a pork chop’ verse by the Two Charlies, that maybe Jim Jackson’s song was ultimately derived from Sam Collins. Or maybe this duo just decided to incorporate Jackson’s line into what was at least a related title. Interestingly, the blues referred to by female singers here, treated the iconic pork chop as part of the rich sexual symbolism that runs through the Blues. Memphis Minnie’s Selling My Pork Chops [Bluebird B 66199] from 1935 is a further example which includes as part of the refrain, “but I’m givin’ my gravy away” (16) Whereas the male singers are regaling the pork chop in a literal sense of its culinary delights, as Alec Johnson sang:

(A possible research road

to stroll down by somebody?). Notes:

References:

Additions/Corrections &

Transcriptions by Max Haymes. Footnote 1: See ‘Unknown Artists - Field Recordings by Milton Metfessel’ on the page quoted, for more detail of these ‘phonophotographic’ recordings. Back Footnote 2: In 1926 the Biddleville Quintette recorded the earliest commercial disc of the song as I Heard The Voice of Jesus Say Come Unto Me And Rest [Paramount 12396]. This and their virtually identical re-make in 1929, with the shortened title, also use the long-metre hymn style. Whereas the Mound City Jubilee Quartette gave a more upbeat, ‘modern’ version in 1935. Back Footnote 3: The issued Take 2 [Victor 21387] is almost identical in lyric and performance to this Take 1. Back Footnote 4: In slavery times, certainly on the larger plantations, often meat of any description was eked out in meagre rations to slaves; sometimes as little as 1lb. every month. The nearest thing to a meat-based meal was usually bacon fat added to turnip or collard greens-officially! Slaves often had to ‘steal’ a hog or chicken (from the ‘master’) which they had raised in the first place! Although there were exceptions at traditional agricultural celebrations such as the aforementioned hog-killing and at corn-shucking time [more on this later] as well as Christmas, etc. Back Footnote 5: This is a different song from Pig Meat Blues [Paramount 12398] by Ardell “Shelley” Bragg which she recorded in 1926. This latter title was covered by pianist Georgia White in 1936 and probably made more familiar to British collectors via versions by Leadbelly as Pig Meat Papa in 1935 and Pigmeat in 1943. And confusingly, Georgia Tom and Tampa Red ‘s Pig Meat Papa from 1929 is a another different song! There’s no copyright in song titles. Back

Footnote 6: Casey Bill’s steel guitar is not audible, despite B.&G.R.

(p.620).

Back

Website © Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White. All Rights Reserved. |