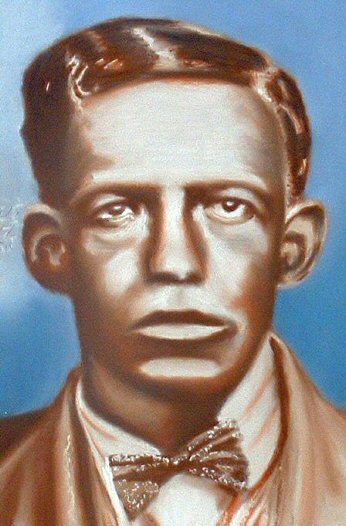

Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Early Blues Interview |

|

Alan: Thank you very much for agreeing to these questions. First of all, what are your musical memories growing up in Huntington Beach, California? Stephen: Well, my musical memories. Originally I heard music Ėmusic was always around when I was growing up. My parents played music, records, all the time, although neither of them were musicians or musical. Both my grandmothers had pianos. My earliest memories include music and my Dad had a hi-fi system that was extremely advanced and the speakers were twice the height of a 3 year old. A big Wharfedale thing and I then latched onto guitar sounds for some reason and it was the Beatles and the Stones that really made an impact. And I was really young, 2, 3 and 4 when I started listening and by the time I was 5 I knew who the Beatles and the Stones were. My mum was even young herself to be a first generation Beatles fan so it was some decades later really, certainly 10 to 15 years later. So, in terms of musical memories, it starts there really Ė I wanted a guitar, then I had some lessons and instantly formed a band. I had a band when I was 8. Alan: Did you then always want to become a musician? Stephen: I think so, yes Alan: What kind of material did you like playing in those early days? Stephen: Whatever one has the kind of capability to play really. Youíre quite limited when youíre 8! I definitely would have played Blues stuff because it seemed easy and accessible to an 8 or 9 year old, the 3 chord thing. You know, the thing that is always held against the Blues by the people who want to knock it, that itís (supposedly) dead simple pentatonic scales, 3 chords that a monkey could play. Idiots with toy guitars could play it. I know we played some Beatles stuff and some Stones stuff, I can remember doing Jumping Jack Flash. Alan: I can remember that coming out. Stephen: I donít remember that but I was picking up on all this later. A great song is always a great song. So, by the time I was 13 or 14, Iíd done enough research and heard enough music to know about proper Blues. Iíd heard Robert Johnson by that stage, Iíd heard Leadbelly, Big Bill Broonzy, Son House and Brownie McGee Alan: Fabulous Stuff! Stephen: Yeah! So, Iíd say that was when my first stabs at playing authentic Blues music occurred. Alan: Tell me about your meeting with Albert King and how he inspired you. Stephen: I lived in Huntington Beach as you know and there was a club there called The Golden Bear which was a place that was a bit like Ronnie Scottís in the sense that youíd eat, get served food at your table but it was also a live music venue. It was on the same circuit in the states as The Whisky A Go Go in Hollywood and was a similar size and structure. The Golden Bear was directly across from the pier on the beach and he played there October or November, which is a really nice time of year in California and there is a massive difference in the weather to what goes on in the Mid-West states, in Chicago or wherever he was living at the time. He did two shows at the Golden Bear and his bus was parked out front and he was sat there, enjoying the ocean view and warm weather, smoking his corn cob pipe on his own in the bus. So I knocked on the door and asked if I could come in and he said, absolutely. So I sat and talked to him for a bit and he had a guitar and showed me a few things. It was all coming so fast and of course I was in complete awe so my capacity to take stuff on board was heightened and his guitar was strung weird so itís all upside down and looking very strange but Iím doing my best to follow. I was over the moon, he was such a great guy. His playing was so other worldly to me, it sounded like nothing else I had ever heard. I was in a daze for weeks, after the first time I heard him. Anyway he helped open my eyes to inventiveness, and finding a unique voice with the guitar. Alan: Who are your favourite Blues artists? Stephen: I have heard The Malchicks recently Ė I like them a lot. Thereís a couple of James Hunter things I think are really great. Iíve heard an Oli Brown tune which I think is really good. Joe Bonamassa I didnít really get until recently when I heard some live stuff which I thought was just amazing, really blew me away. Blind Willie Johnsonís vocals are just outrageously amazing. Skip James was just so genius. Alan: It takes a while to get into him, with his voice. Stephen: I really like his voice. But even more than Robert Johnson, the counter-rhythms that go on in his guitar playing are just so advanced. Itís really astonishing.

Alan: Who influenced you the most in your music writing and playing? Stephen: The Beatles, definitely, because they knew how to structure a song. But equally somebody like Captain Beefheart who also knew how to structure a song but completely in his own inimitable fashion. In terms of soloing Ė everybody! Freddie King, BB King. Eric in the Mayall/Cream period, which I think is untouchable and is just right up there with anything, Hendrix or anything. Just astounding. He was structuring solos at a new level, when at that period in popular music you just had people mimicking the choruses of songs or something to do with the melody of a vocal line, such as George Harrison did a lot. Or you had those freakouts, like Dave Davies did which were all pretty one-dimensional, on one level. Then, Eric came and was able to follow his head, musically speaking. Alan: What was the best Blues album you ever had? Stephen: How about a few? Firstly, BB King, Live at Cook County. Then thereís The Beano Album [John Mayall's Bluesbreakers with Eric Clapton]. A constant favourite to this day is The Crusade album [John Mayall], the Mick Taylor album. I knew that people didnít really demonstrate on the streets for the Blues but putting it on the cover was just so genius. Mick Taylorís playing is great on the album, you know, his tone & touch and soulful vibrato were a massive inspiration to me. ďThe Death of J B LenoirĒ haunts me still. Itís such a moving song, sung so well, great melody. I discovered the album at exactly the right time in terms of unlocking loads of puzzles. For example, Skip James was doing all this complicated stuff and a lot of it was indecipherable to me, so I would approximate. But when I heard the stuff that Mick Taylor was playing, for some reason it was very clear to me and I could figure it out. Also, I began to notice that when you play stuff on different parts of the neck it gives you a difference in the timbre and the tone. So you can play a phrase on a high E string down at the bottom of the neck or you can play the same phrase further up and it will have a whole different tone, texture and intensity, and thatís when I began to develop the ability to hear where people were playing on the neck. So, once I started to be able to play solos as the people who composed them had played them, I could see how they had been constructed and could kind of get into their head for the moment of that solo. Itís never going to be exact but I started to get glimpses of how these people did it. The Crusade album was huge for me. Then, ANY Albert King album. With The Crusade album, Iíd feel good and it filled in huge gaps about what I was striving for and what I could actually achieve. But then Iíd hear Albert King and just think, ďIím lost. I thought Iíd made great progress but Iím lostĒ. So you have to regroup, re-approach and come at it from a different angle. You think youíve got some degree of proficiency and you feel comfortable, and you can hear that youíve really made some progress but then somebody like that comes along and it just blows you into a scorched earth, bleak state of mind. So, thereís no ďbestĒ album, but thereís loads of them, and it still goes on. Alan: Absolutely. And itís a great journey Stephen: Yes! Thatís the beauty of music and especially the beauty of the guitar. Keyboards are fixed and you canít bend notes. Synthesisers can begin to sound so plastic that I donít even consider them music but the guitar is so expressive with all the ways you can tune, finger and slide. It might sound technical, and I suppose it is, but another way of saying it is that itís never going to get boring if Iím both always learning from the past Blues masters AND open to exploring the unknown - sounds, textures, amps, recording techniques Ė everything. Alan: I was going to ask about your favourite instrument but youíve already answered that. But I believe youíve got a Gibson? Was it made to your spec?

Stephen: Yes, I have. The blue Firebird I was playing last night was custom-made. I sent Gibson a Les Paul with my favourite neck on it and they scanned that and made a replica neck with the same dimensions for the Firebird. I sent them a block of wood painted the colour I wanted it and they did it. The colour is a one-off and the wiring is different on it too. I love the drums too. Albert King was apparently a professional drum player before the guitar and I think thatís one of the reasons why his phrasing was so spot-on. Alan: Are there any particular songs that you play that have special meaning to you? Stephen: As The Years Go Passing By has come to have certain meaning and Iíve been in that position of, ďthereís nothing I can do if you leave me here to cryĒ. I can step into that perspective of the lyric, almost like a script, and I bring very personal, real experience to it. Itís not me just singing a song. UmmmÖIíve been the person leaving too, so I know it from both sides. Alan: What brought you to the UK? Stephen: Music! Specifically, the British Blues. I was just speaking to Jimmy Page about this and I said to him that he might have a different opinion (he didnít really) but I think that the Beatles did blues-based music, derived from the Blues. The early ďSaw Her Standing ThereĒ and ďCanít Buy Me LoveĒ are Blues songs. Pop choruses are just bolted onto the Blues progressions. ďSheís a WomanĒ is the same thing. ďI Feel FineĒ is a Blues song with a pop chorus. I knew that they were really influenced by Chuck Berry and at that stage I thought that Chuck Berry was a rock n' roll guy because that was how he was marketed, but when I discovered that he was on Chess and I started to look at who else was on Chess, then I was away with realising that the Stones did Chuck Berry stuff and were ALSO name-checking Bo Diddley, John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf. Even though it was years later, as a 9 year old Californian kid seeing the reverence that the UK musicians had for these guys made a big impression on me. Strange as it may sound, to start with I only felt a part of this music I was hearing by the British bands. Even though it was two decades down the line, the album covers I saw from Cream for example were aimed at youth but the album covers I was getting for, say, Cook County [BB King], (which were about as trendy as it got) Ė it was that sort of bitmapped image, some treatment they did to a photograph, but most of them looked like scholastic library issued recordings (and, of course, many of them were.) They spoke to me only of austerity and adult and were impenetrable in a certain way. So all that marketing they did on the 60ís stuff was still working on a younger person down the road and I did take note that all these guys were British and I also knew that the Stones were on some Beatles sessions etc and I really was drawn to that because the music was so magical. I know that in the 60ís in the UK there was a whole thing going on about authenticity and Iíve spoken to the likes of Jeff Beck about it who said he just felt guilty taking the music. But what was going on for me was that it was British music that was steeped in and saturated with Blues and Blues sensibilities. I had no aspirations to go and hang out in Chicago. As a young teenager Iíd been driven through Alabama and the southern states and didnít want to go and hang out in the Mississippi Delta. The UK was more exotic. A different country is always more exotic than your own country. Alan: Who impressed you musically when you first came to the UK? Stephen: I was quite disappointed when I first came to the UK. I came here with a huge image, and fantasy, about what it was like. I didnít really think that people would demonstrate for the Blues on the street but that was one little component of a huge thing that Iíd already constructed by the time I arrived here. So the stuff that was in the charts, I thought was horrific and synthesisers were still quite prominent when I arrived in the 1980s and I was also disappointed by what had happened to the Blues in this country, that it had been put into a specialist ghetto, and was being treated as an uninteresting footnote in the musical story of the UK. There should be statues to people like Alexis Korner, Cyril Davies and Chris Barber. Graham Bond, John Mayall Ė there are many more. People just seem to do down their own country. Alan: How healthy do you think the Blues scene is in the UK nowadays? Stephen: I think itís getting really quite strong and there are definite signs of an impending breakthrough into the mainstream, which I think will really be a great thing. Itís getting easier, I donít feel that I have to apologise for being Blues. I remember being on Billy Butler BBC Radio Merseyside - it made for good radio and I was being sincere, but in the end he would name an artist and say ďBut youíre going to tell me thatís Blues based, arenít you Stephen?Ē. But the fact is that even punk is rooted in the Blues. I did see the Pistols on the night they broke up in San Francisco. Iíve no idea what the consensus is or isnít on them, but [Sex Pistolís songwriter] Glen Matlock says he just sped up Blues songs & progressions. I know The Clash were Blues fans and theyíve got loads of Blues songs, and some of it might sound rockabilly but again we're talking about the Blues sped-up. Alan: How do you think the British Blues Singers impacted the Blues? Stephen: I consider the contribution that British music has made to The Blues, equal to that of the pioneers, equal to Son House, to Skip James. Absolutely equal. Alan: How did you get to play alongside Eric Clapton, and did he inspire you in any way? Stephen: Mutual friends. When I was a teenager he floored me, completely inspired me, and still can. Particularly, the Mayall album, and even more the first Cream album when he was set loose. Ginger and Jack were coming from this jazz background and improvising and letting it go, and I find Ericís work on the first Cream album astounding. Itís beautiful and genius, tough and ruthless. Alan: Tell me about your busking days. Did you feel you were following the steps of the old Blues men? Stephen: Yes, it was the way that I talked myself into going down there (into the London Underground). I didnít really want to do it but knowing that so many of the Blues legends had busked made it more palatable for me. Personally it seemed a definite step, even 10 steps, backwards at the time. I was asked about it recently in an interview but when it was printed the journalist said, ďYes, it was great that he went down in the Underground bla bla but Tottenham Court Road is not as edgy as Memphis in 1948Ē, and I thought, ďWell, how would you know?Ē He wasnít there was he? And his image of Memphis in 1948 is one thing, not unlike my image of England before I arrived here Ė I had no way of knowing. And the other thing thatís missing from that journalistís view is that I was at a dead end in my life. Iíd been recording and touring, and I had a contractual situation which had hit a dead end and I was lost as to what to do, drugs and alcohol were featuring too heavily in my life at the time, I had no sense of direction or purpose, so busking seemed to tick a lot of boxes, and solve a lot of problems. You know there were periods when I had nowhere to live. It might be that the journalist thought I was trying it on, like a fashion statement or something, but I wasnít doing it because I thought it was cool & trendy and it could be tough, very, very tough. In the end what seemed to be a rather humiliating turn of events was in fact a catalyst for me, a reconnecting to my roots. It was sustenance. Alan: A lot of British stars started by busking.

Alan: I bet it cost a bit! Stephen: Well, yes. I found I had to continue busking to fund it. But it also meant I could take time, it wasnít a rushed job and I could be relaxed and breathe. I had some perspective on it. Alan: To quote, ďThe New Blues revolution thatís a predominately UK based musical phenomenonĒ. Tell me more. Stephen: Youíve now seen the live set twice. The album is something that I did before this live situation developed, so some songs, like the one we open with (The Gun Song) is a song that goes in a whole new direction; it started as ďAlexies Korner SaysĒ from Guitararama, and is now itís own entity. So New Blues is just that Ė itís a way of describing Blues in 2009, itís a way of describing the ethos that blues music is a breathing, living organism, itís not a museum piece, itís not meant to be sealed in aspic and also itís a way of speaking about an atmosphere that says Blues is meant to be that way. Knowing about what the music was and getting inside early blues music is hugely, critically important, you know really feeling it, but itís a pointless exercise unless it has relevance to today, because otherwise itís just a museum piece, just a curiosity or artefact. Alan: Yes, and itís getting it to the younger generation. Stephen: I think the White Stripes had a period when they were doing that. The Black Keys have done that; itís nice to see Seasick Steve getting on and I know lots of kids love the music. When I was busking I had instant market research and I would get stopped by kids all the time who had no idea they were listening to Blues and they would say ďWhat is this? Itís fantastic!Ē. To them, it was just guitar music and then theyíd say, ďI never really thought I liked Blues musicĒ. Itís somehow happened that Blues has been segregated on all levels Ė retail, live, radio, media Ė and pushed into a specialist niche. In 1968, in the charts, you had Zeppelin, Hendrix, Cream, Fleetwood Mac in the charts. It was stunning stuff and thereís no reason why that couldnít happen again. By the way, thereís nothing wrong with pop charts Ė itís only short for popular. Blues is like a well of pure music that you can go back to at any point, wherever you are. People will be able to do this in 2050 but it requires that you turn loose of all your sensibilities. You canít keep one foot in modern life, musically speaking. It requires of you that you surrender your musical points of reference and that you are back there with Son House, which also means getting used to the way the old recordings sound. You listen to the Kaiser Chiefs or Alicia Keys or Leona Lewis or Britney Spears or Duffy or Amy Winehouse or a even a new Buddy Guy recording and the actual technique of recording sound has changed, in the way that the sound engineers are doing it, itís so compressed and so dense and people get accustomed to hearing things that way and everything else sounds wrong. Alan: You did a tour of universities Ė The BLUnivErSity Tour. How did that go? Stephen: It went really well. We generally tied it in with a gig in the town. Iíd love to do it again. Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Howling Wolf, Willie Dixon etc were all one man campaigns for the Blues. Again, perspective is everything but I got into John Lee Hooker quite early on and I always took it as read that he was a fixture and always had been, but it turns out that he had huge chunks of time when he was wandering in the wilderness. When he moved to Detroit, they wanted more sophisticated stuff than what he did, plus they considered him old hat, and he had to play in a shabby club at the end of the road. There's a whole road dedicated to live music in Detroit that he describes. It took a good while for him to establish a beach head. Muddy Waters and BB King had the same thing, and couldn't get a look in either initially, so they all had their struggles against prevailing attitudes. The University thing is just another way of doing it, getting the message out about Blues and the students love it. It was described as a Masterclass but was really part politicianís speech, a bit of a preacherís sermon Ė all for the Blues you know, and then there was a live performance bit and then I would have a section with historical content like, ďEven now, in 2009, The Mississippi Delta still has the highest level of poverty in America". Alan: Absolutely. I toured for a month last May and it really opens your eyes. Stephen: Yes Ė and it still has the greatest infant mortality rate in America, black or white. Share-croppers were 40% white on the plantations, it wasnít all black families. By the way (Barack Obama took office the week before this interview) I do love the fact that Obama is in the White House. For Blues music. If he can be in the White House, I just see it as a road sign that things have finally opened up. Something about a black president that seems so huge & symbolic. What would Charlie Patton say about it , you know? What song would he write? Anyway, if you are a guitar player and you donít get steeped in the Blues, as far as Iím concerned you might as well be playing with one finger less. It doesnít matter if you want to be a slash metal guitar player, or a jazz guitar player Ė all the techniques were pioneered by Blues guys, even the fact that we have distortion now, itís taken as read that sounds are distorted Ė the Blues players sought it out, they actively and consciously aimed for it. They were the first to do that. Sometimes because they had equipment that led them, perhaps they had a cheap amp that gave them the sound but whatever it was, they knew it worked. Musicologists studying musicians in Africa were astonished to find that theyíd take something like a flute, which has a very pure tone and theyíd dirty it up. The kazoo came from a process of seeking out a dirtied-up, distorted sound for rituals which they would wear a mask for, with a metal mouthpiece in the mask. In the context of popular music in the west in 2009, you trace it back and get stuck into the Blues and itís the only thing that makes sense to me. Alan: So, your tour in May with Mick Taylor. How did that come about? Stephen: Somebody was talking about having a special guest and I thought of a few people and he was the one guy I just thought, ďHeís fantasticĒ. It turned out we were playing a club in London a week after he was playing the same club so I went down to see him and it turned out that I know Mickís manager and so itís just come together. Alan:. Iím really looking forward to this tour. Stephen: You and me both! Alan: Finally, what are your future plans. New album coming out? Stephen: Yes, we are recording just up the road from here. We are hoping to get it finished by April and releasing it in June. Alan: Got a title for it yet? Stephen: Not sure. Well, I do, but Iím not yet ready to commit to it. But Iím really excited about it because Guitararama was me with various musicians, but this is an album with a band and weíve been playing now for 18 months and some of the new songs have been played on stage many times and you can hear in the recordings that they are road tested. Itís a whole other dimension thatís been added with the band functioning as one organism. Alan: Stephen, thank you so much for your time. Really appreciate it. Stephen Deale Petit on tour with Mick Taylor - Photos Skegness Rock & Blues Festival 2009 - Photos Story board from Stephen (a series of ongoing 1 minute story clips which will make up a complete story board):

Stephen

releases his new

single 'As The Years Go Passing By' on June 15th via 333 Records.

His last single A Better Answer has just been named Track of the Day by Classic Rock magazine

Return to Blues Interviews List

Website, Photos © Copyright 2000-2009 Alan

White. All Rights Reserved. |