Painting © 2004 Loz

Arkle

Website

© Copyright 2000-2011 Alan White - All

Rights Reserved

Site optimised for Microsoft Internet Explorer

Catfish Blues (Origins of a Blues)

By Max Haymes

This blues reached a peak of popularity in the Mississippi Delta during the late 1930s and prior to World War II. The sensual haunting melody was later recorded by a world-famous Delta singer in 1950 (arid subsequently by other singers) and re-titled “Rollin’ Stone”. This was of course, Muddy Waters. As Texas blues expert Mack McCormick said singers like Muddy and Elmore James “worked the catfish theme into a separate song”; (1). But we are jumping ahead of the story.

“Catfish Blues” was another example of animal-symbolism in blues which according to Paul Oliver (see “Screening The Blues”) extended along the lines of the ‘black-snake’ motif made famous in recordings by Victoria Spivey and Blind Lemon Jefferson in the 1920s; interestingly, both from the state of Texas. Blues singers adopted the persona of animal-like characteristics, which is how most Southern whites perceived the blacks, using that persona for powerful, sexual imagery.

Blues lyrics reflect, generally speaking the singer’s environment and fried catfish along with fried chicken has “been a part of the southern diet for two hundred years.” (2). Found in both fresh and salt water, the bewhiskered catfish, growing up to 150 lbs. would have been familiar to black fisherman in the interior and on the Gulf Coast and especially in the concentrated black-populated areas in Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama, with their network of rivers including the Tombigbee and the mighty Mississippi. Yet the catfish did not appear in blues lore, as far as is known, until the popular, black medicine-show entertainer and songster, Jim Jackson included it in a 1928 recording for Vocalion. This was Part 3 of his monster hit “Jim Jackson’s Kansas City Blues”. The third verse runs:

“I wished I was a catfish, swimming down in the sea;

“I wished I was a catfish, swimming down in the sea;

I ‘d have some good woman, fishing after me.”

Ref: “Then I’ll move to Kansas City,

I’ll move to Kansas City;

I’ll move to Kansas City,

Babe, honey, where they don’t ‘low you.”(3)

Parts 1 and 2 of this record had been issued some 3 months earlier and “reputedly sold 1,000,000 copies! This would thus make it one of the very first gold records” (4). This success prompted Vocalion and Jackson to cut a total of six versions by the end of 1928. The last two as “I’m Gonna Move To Louisiana”. But the ‘catfish verse’ only appeared in Part 3, quoted above. Two of the most well-known ‘cover’ versions included one by the Memphis Jug Band as “Kansas City Blues”, made some 3 weeks after Jackson’s best-selling Part 1; and archetypal Delta bluesman, Charlie Patton recorded it as “Going To Move To Alabama” in 1929. But both records omitted the ‘catfish verse’. However, between these dates another Delta singer, William Harris, did include a variation in his “Kansas City Blues” which became standard in later versions of “Catfish Blues”/”Rollin’ Stone”:

“I wish I was a catfish, swimmin’ in the deep blue

sea;

I’d have all you women fishin’ after me.”(5)

Apparently, Jim Jackson had introduced “Kansas City Blues” to “many potential record buyers before the record was issued” (6) on the medicine show circuit in the Southern states. The singer was born c.1884 in Hernando, Miss. on the Illinois Central line; that’s in De Soto County. So quite conceivably, he was singing about the catfish in 1919 or thereabouts. In any event, about a week after recording Part 3 of his million-seller, Jackson moved to Memphis, Tenn. (sane 15 miles from Hernando) to live. By now he was one of the most popular black singers on Beale Street and throughout the whole of the South. Ex-member of the Memphis Jug Band, Dewey Corley, remembered “I used to see Jim on stage in medicine shows. There was a gang of people behind Jim as long as a freight train (Jim was the star of the show). They used to set up their tent in South Memphis. It was just like a carnival”. (7)

So one or probably all the versions of Jackson’s “Kansas City Blues” (in reality the first 4 recorded “parts” were most likely the summation of one continuous live performance) were not only well-known in many areas of the South, but known for some considerable time prior to them being put on disc. Despite all this exposure to a black listening public the catfish symbolism didn’t take off immediately, at least on record. The same could be said for the fish motif generally.

Ma Rainey had cut “Don’t Fish in My Sea” as early as December1926, but it is quite likely she would have heard Jim Jackson many years prior to this, as she also traveled the medicine/tent-show circuit throughout the South in the same period of time that he did. In the same month that Part 3 of “Jim Jackson’s Kansas City Blues” was recorded, an East Coast guitarist, William Moore, included an intriguing “Catfish Woman Blues” in his only record session c. January 1928. Unfortunately, this was never issued and accounts for one of the many lost Paramount masters. Again it seems like that Moore was inspired by the immensely popular Jim Jackson record. Not until 1934 when Tampa Red declared:

“Now, I’m a kingfishin’ poppa, an’ I know what kind

of bait to choose;

Unk. Female (speech) “Yeah!”

I’m a kingfishin’ poppa, I know what kind of bait to choose.

That’s why so many women cryin’ those ‘Kingfish Blues’” (8)

was the world of fishing adopted by the blues singer, adding to the already rich vocabulary of sexual symbolism. The following year, Bumble Bee Slim from Georgia (as was Tampa) recorded “Everybody’s Fishing” on the Vocalion label:

“I woke up this mornin’ an’ I grabbed my pole

Can’t catch the fish to save my soul.”

Ref: “Everybody’s fishin’ – yes, Everybody’s fishin’;

Everybody’s fishin’, I’m gon’ fish some too.”

“Every little fish like this bait I got,

My babe home got her skillet hot.”

Ref: “Everybody’s fishin’” etc. (9)

St. Louis-based singer, Alice Moore, took the closing phrase of Slim’s refrain as the title for her 1936 version “I’m Going Fishing Too”. Meanwhile, the catfish imagery had been evolving around Greenwood Miss. and approximately 100 miles away in Lake Cormorant, Miss., Delta bluesman, Fiddlin’ Joe Martin, was to reproduce his version of the Bumble Bee Slim number as “Going To Fishing” for the Library of Congress in 1941. The same year that “Catfish Blues”/”Rollin’ Stone” was to make its recording debut.

References (Part 1)

1. McCormick Mack. Notes to “Blues In My Bottle”

L.P. Lightnin’ Hopkins. Prestige Bluesville BV 1045. 1984 (Reissue).

2. Ferris William & Charles Reagan Wilson (Co-Eds.). “Encyclopedia Of Southern

Culture”. p.616. University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill & London. 1989.

3. “Jim Jackson’s Kansas City Blues-Pt 3”. Jim Jackson vo. gtr. Sunday 22nd.

Jan. 1928. Chicago, Ill.

4. Rijn Von Guido & Hans Vergeer. Note to “Kansas City Blues” L.P. Jim Jackson.

Agram AS 2004. c.1977.

5. “Kansas City Blues”. William Harris vo. gtr. 9/10/28. Richmond, Ind.

6. Rijn & co. ibid.

7 . Ibid.

8. ”Kingfish Blues”. Tampa Red vo. gtr. Black Bob pno. 22/3/34. Chicago.

9. ”Everybody’s Fishing”. Bumble Bee Slim vo. ;poss. Horace Malco1m pno.; Big

Bill Broonzy gtr. 27/2/35. Chicago.

Cotton-Packet

1878

Cotton-Packet

1878

Catfish Blues Part 2

Although Cowley rightly says “Catfish Blues” is “...an enduring Mississippi blues theme that dates, on commercial record, from 1941 (and) it was first recorded by Robert Pettway” (sic) (1), this only tells part of the story. It had for a long time been associated with the rough-voiced guitarman Tommy McClennan. Both singers were from the Greenwood area in the Mississippi Delta. A younger Delta singer, David ‘Honeyboy’ Edwards, told “Blues Unlimited” magazine in 1968, that Tommy McClennan was “.. . playing the same things he made (i.e. recorded), “Catfish” and “Bullfrog”. Ha. ha. Playing pretty much the same way he did on his records, yeah, same way, same things”. (2)

‘Honeyboy’ is referring to McClennan’s “Catfish” on which the latter only mentions the bullfrog. Said Tommy in 1941:

“I wants to make this one right.

This is the (best) one I got.”

Then he hung his head an’ went to singin’ an’ cryin’:

“Now, I wished that I was a bullfrog, swimmin’ in that deep blue sea.

Lord, I would have all these good lookin’ women, now, now, now, fishin after

me.

Fishin’ after (guitar completes line)…

I mean after …..

Sure nuff, after me”. (3)

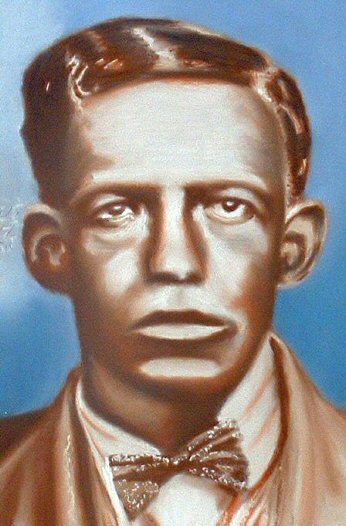

Tommy McClennan. c.1940.

McClennan's rasping vocal veering between the menacing and the sensual, in the familiar dark melodic strains that have become associated with this famous blues. His spoken self -encouragement might refer to the fact he featured slide for the only time on a record, or that this was his most popular number in the jukes and barrelhouses in the Delta. As' Honeyboy' says "When he played his style the people liked it. He had a big mouth and could holler a whole lot. I learnt "Catfish Blues" & " Hard Headed Woman Blues” (probably “whiskey Head Woman” from McClennen’s 1st. session in 1939), and a few numbers he made." (4). And Calt & co. state "Although Petway's was the original recording of "Catfish" Blues" under that title,...the song had been McClennan 's signature piece around Greenwood”. (5)

Robert Petway played with McClennan on many of his gigs. Petway had a similar style, in both vocal and guitar, to Tommy, which Edwards deemed 'different' (i.e. new at the time). "It'd be in and out; sometimes Tommy would be by himself and then when he get something pretty large he'd go get Robert."(6). Tommy McClennan, who was better known, had moved to Chicago and started recording for the Bluebird label in 1939. It would seem that after enjoying a few "hits" he sent for Petway who had 2 sessions in 1941 and 1942. Petway's first side was his version of the "Cat fish Blues" theme; taken at a much faster lick on his National guitar, but without the bottleneck:

“Well, if I was a catfish, mama?

I said, swimmin’

deep down in, deep blue sea

Have these gals now, sweet mama, settin’ out

Settin’ out hooks for, for me, settin’ out hook for, for me

Settin’ out hook for, for me, settin’ out hook for me

Settin’ out hook for me, settin’ out hook for me.” (7) (17)

A superb dance-oriented version this record introduces an early example of the “fade-out” technique (almost unique in pre-war blues records). Petway was a better guitarist (on record) than McClennan, while the latter “could beat him hollering” (8).

Robert Petway. 1941.

Robert Petway, judging from his photo, was about the same age as McClennan (about 33 when he cut “Catfish Blues”) and Big Bill Broonzy told Paul Oliver that they “.. . were in there together - kids together, grew up together. But Tommy got better known.”(9). Perhaps Petway in an effort to get from under McClennan’s shadow in the Delta, consciously sought to ring the changes, with his version of “Catfish”. Speeding up the tempo, abandoning the slide, and using different verses (except for the one already quoted) would seem to indicate this. Sometimes hailed as the definitive example of this blues on record, it has rarely been attempted by other blues singers. They generally use the ‘slow ‘n sultry’ more traditional style which was popularised by Tommy McClennan.

In 1960, Paul Oliver recorded a young Delta singer, Robert Curtis Smith on location in Clarksdale, Miss. One of his songs was “Catfish”. Smith, who had an original driving style on guitar, adopted a similar tempo to Petway but in a vastly different format. He used most of Petway’s verses and a couple from McClennan. When he let the guitar speak on its own, however, it was all from Tommy. From emulating his under-played slide part (with “naked” fingers) to his solo in the break.

Of course R. C. Smith was probably influenced by a record made some ten years earlier, by one-time fellow resident, Muddy Waters. Muddy featured on vocal and guitar, followed McClennan’s musical format (again without slide) and used Petway’s verses + a couple of others. One of which gave the song a new title “Rollin’ Stone”. In 1961, another Mississippi singer recorded “Catfish Blues” but did not include the title in his song. K.C Douglas injected some original verses while approximating the style and rhythm of Robert Curtis Smith.

Of course, by the time Douglas and Smith recorded, the blues had become electrified. Muddy’s rare vo. gtr.(by 1950) outing ”Rollin’ Stone”, significantly used an electric instrument. Not surprisingly, a ‘city blues’ style “Catfish” cropped up, in c.1969 by Cousin Leroy. Containing a doomy, echo chamber with bass, drums and atmospheric guitar, the lyrics concentrated on the singer going down to crossroads to exchange his soul, with the Devil, for a guitar style. Incorporating Muddy’s ‘rollin’ stone’ verse, Leroy used Tommy McClennan’s guitar phrasing from 1941

In 1979 the clock turned almost full circle when ‘Honeyboy’ Edwards recorded for Folkways on acoustic guitar and included a “Catfish Blues”. Also using the ‘rollin’ stone’ verse he came closest to Robert Petway via his vocal approach and faster tempo. But the guitar phrases (for the most part), including the instrumental break, go back to Tommy McClennan and “Deep Blue Sea Blues”.

Catfish Blues”/”Rollin’ Stone” “ ... seems to have originated with a group of players based in and around Bentonia, in the southern part of the state”. (10) This group would have included Skip James who was born in Bentonia, Miss. 1902. Calt & co. point out that “Catfish Blues” was evidently “already traditional when Petway recorded it. Skip James having performed the same song in the 1920s.”(11). Bentonia was some twenty miles from Yazoo City (near McClennan’s birthplace) and 60-odd miles from Greenwood, Le Flore County which was McClennan’s base for many years until he moved to Chicago in 1939.

James who was 6 years older than Tommy could well have been in at the start of a blues tradition in the 1920s. However, the origins could lie further north in Mississippi, in the Hernando area, where Jim Jackson was born. Jackson being first on record with the ‘catfish blues’ verse in 1928, which he included in Part 3 of his huge-selling “Jim Jackson’s Kansas City Blues” on Vocalion. (see “Catfish Blues” Pt.11 in “A.B.”No.8). Jackson was primarily known for his medicine-show/minstrelsy and hokum material, being born some 12 years earlier than Skip James, c.1890. Intriguingly, a male duo, billed as “Swan & Lee” cut just 2 sides in 1929 very much in the hokum style, with humming, Mills Bros.-type scat singing and sexually slanted verses. One song included 2 verses with reference to a catfish. One of which ran:

“Catfish’ll have kittens, I’ll tell you Jim,

When old Tom Cat learns how to swim.

Ref: He’s a fishy little thing,

He’s a fishy little thing.

He may look suspicious,

But he’s a fishy little thing.” (12)

Maybe an unrecorded singer picked up on the catfish symbolism on the medicine show circuit via Jackson and/ or Swan & Lee, and took it to Bentonia where it was incorporated into a hard Mississippi Delta blues. Whatever it’s starting point, “Catfish Blues”/ “Rollin’ Stone” has proved one of the most durable blues “standards”. It has even been recorded by Texas postwar blues bard, Lightning Hopkins. McCormick said that “Catfish” grew from “a verse that was long a part of songs like “Easy Rider” (13). However one of the earliest blues singers, Blind Lemon Jefferson, also from Texas, did not include any reference to a catfish on “Easy Rider Blues” from 1927. Neither did vaudeville/hokum singer Frankie ‘Half-Pint’ Jaxon on his version 2 years later, with Tampa Red’s Hokum Jug Band.

It’s tempting to make some connection between Hopkins’ use of a verse not found on any other record of “Catfish” which harks back to another song from 1928,and Jim Jackson. Lightning sings a variation of these lines:

“If a white man have the blues, he goes down to the

river and sit down. (x2)

An’ if the blues overtakes ‘im, he jumps overboard an’ drown.”

“If a coloured man have the blues, he goes down to the river and sit down. (x2)

If the blues overtakes ‘im, he thinks about his woman an’ come on back to town.”

(14)

Using a couple of Petway’s verses but McClennan’s slower rhythm, the Texas man ‘Hopkinised’ his version of “Catfish”(c.1961); yet retained that insistent Delta feel. Hopkins partly combined both of Jim Jackson’s verses into one:

“You know, I went down to the river,

Start to jump overboard an’ drown;

I thought about that little woman,

I turn around, I went walkin’ back to town.

Mm. Back to town.

Mm. Back to town.

Sure nuff, mm, back to town”. (15)

But that’s the Blues!

References (Part 2)

1. Notes to “Bluesville Vol.1- Folk Blues”. L.P. Ace

Cl-I 247. John H. Cowley. 1988.

2. David ‘Honeyboy’ Edwards: interview with Pete Weiding. “Blues Unlimited”

No.54.June, 1968. p.7.

3. “Deep Blue Sea Blues”. Tommy McClennan vo. gtr., speech. unk. bs. 15/9/41.

Chicago, Ill.

4. David ‘Honeyboy’ Edwards: interview with Dave Peabody. “Folk Roots”

No.78.Decernber, 1989. p.31.

5. Notes to “Lonesome Road Blues-15 Years In The Mississippi Delta. 1926-1941”.

L.P. Yazoo L-1038. Stephen Calt & John Miller. c.1975.

6. ’Honeyboy’ interview: B.U. Ibid.

7 . “Catfish Blues”. Robert Petway vo. gtr. 28/3/41. Chicago, Ill.

8. ‘Honeyboy’ interview: Folk Roots” .Ibid.

9. “Blues Off The Record”. Paul Oliver. The Baton Press. 1984. p.87.

10. Notes to “Mississippi Delta Bluesman.” L.P. Folkways FS 3539. Robert Palmer.

1979.

11. Calt & Miller. Ibid.

12. “Fishy Little Thing”. “Swan & Lee”. Male duo vo.; acc. unk. gtr. 28/9/29.

New York City.

13. Notes to “Blues In My Bottle”. L.P. Prestige Bluesville. BV 1045. Mack

McCormick. 1984. (reissue).

14. “My Mobile Central Blues”. Jim Jackson vo. gtr. 30th.Jan. or 2nd.Feb. 1928.

Memphis, Tenn.

15. “Catfish Blues”. Lightning Hopkins vo. gtr. c.1961. Houston? Tex.

16. Pre-war discographical details from “Blues & Gospel Records, 1902-1943”.

R.M.W. Dixon & J. Godrich. Storyville. 3rd. Ed. 1982.

17. Lyrics corrected 06/1/21 - thanks to Jean Compton for pointing it out.

Copyright © 2004 Max Haymes. All rights reserved.